Panjandrum

A wonderful story is told about the origin of this mock title for an imaginary or mysterious personage of much power or a pompous, pretentious or self-important person in authority.

Samuel Foote

In 1753, the actor Charles Macklin retired from the London stage and opened an entertainment in Covent Garden that he called the British Inquisition. At seven o’clock every evening this featured a lecture by Macklin followed by a debate. These became popular for a while; so much so that a playwright and fellow actor named Samuel Foote was provoked to attend.

Among his many accomplishments, Foote was a master mimic, aided by a devilishly sharp wit; he seems to have barracked Macklin without mercy. Macklin was unwise enough to claim as part of a lecture on memory that his own was so highly trained he could remember any text he had read just once. Foote is said to have composed on the spot as a challenge a bit of nonsense that has since become famous:

So she went into the garden to cut a cabbage-leaf to make an apple-pie; and at the same time a great she-bear, coming up the street, pops its head into the shop. “What! No soap?” So he died, and she very imprudently married the barber; and there were present the Picninnies, and the Joblillies, and the Garyulies, and the grand Panjandrum himself, with the little round button at top, and they all fell to playing the game of catch as catch can till the gunpowder ran out at the heels of their boots.

Quoted in Oliver Cromwell, Daniel De Foe, Sir Richard Steele, Charles Churchill, Samuel Foote, a book of biographical essays by John Forster, Third Edition, 1860. This volume also includes the detailed story I’ve outlined.

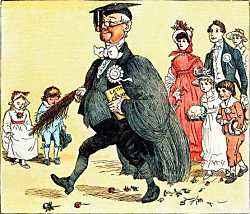

One of Randolph Caldecott’s illustrations for The Great Panjandrum Himself, a children’s picture book based on Samuel Foote’s text, c1885.

It is said that Macklin was so indignant at this nonsense that he refused to repeat a word of it. Most of Foote’s invented words in this piece vanished as quickly as they appeared, but grand panjandrum survived to become a part of the language, no doubt because of its cadence and internal rhyme, and was later shortened just to panjandrum.

There is a problem with this story. The text became widely known only much later, from about the middle of the nineteenth century. Its first appearance in print was in 1825, in a novel by Maria Edgeworth, Harry and Lucy Concluded, in which it is quoted as a test of memory and attributed to Foote. Though it was presumably by then well known, nobody has turned up an earlier written version.