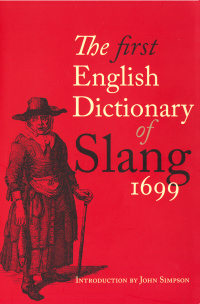

The First English Slang Dictionary

This is a republication by the Bodleian Library, Oxford, of a work of 1699 whose full title was A New Dictionary of the Terms Ancient and Modern of the Canting Crew, in its several Tribes of Gypsies, Beggars, Thieves, Cheats Etc. You might argue that the title of this work is an error, since the word slang was unknown to its anonymous compiler (it was first recorded half a century later, in 1756).

John Simpson, the Chief Editor of the Oxford English Dictionary, notes in his introduction that the canting crews of the title were semi-organised bands of rogues who preyed on people; though gypsies were included in the list, these were almost certainly fake Romanies who adopted the characteristics of true gypsies as a cover. Though the work was promoted as a glossary of the secret language (cant) of marginalised and disparaged groups who lived outside the law, its author built on a small core of such words by adding a lot of more general non-standard English. It included military and naval slang and colloquialisms that we would now class as slang but which often had some connection with artifice, sham and deceit.

Because it’s in the nature of slang to be evanescent, little of the vocabulary the author listed is still current, though delight comes from learning of dandyprat (a puny fellow); cackling-fart (an egg); peeper (a mirror, a looking-glass in the author’s words); Grumbletonians (“Malcontents, out of Humour with the Government, for want of a Place, or having lost one); and owlers (“those who privately in the Night carry Wool to the sea-coasts, near Rumney Marsh in Kent and some creeks in Sussex &c. and Ship it off for France against Law”); the risks of walking unlit city streets after dark are illuminated by moon-curser (“a Link-boy, or one that under Colour of lighting Men, Robs them, or leads them to a gang of Rogues, that will do it for him”. But recognition is sparked by other entries: haggle is defined disparagingly as “to run from Shop to Shop, to stand hard to save a Penny”; humptey-dumptey reminds us instantly of Lewis Carroll, but before it became the short and dumpy person of the nursery rhyme it was slang for ale boiled with brandy; red-haired people were even then being called carrots; carouse was clearly still non-standard; and a mawdlin was a weeping drunk, from references to images of Mary Magdalene crying — much later this led to maudlin in the sense of weak or mawkish sentiment.

The continuing value of this compilation is not just its historical interest, but the insight that it gives into the urban life of the period, which would seem to have been insecure or even dangerous. Indeed, the author remarks that by understanding the vocabulary he has collected, readers might “secure their Money and preserve their Lives”. Words have power, indeed.

[The First English Dictionary of Slang 1699, with an Introduction by John Simpson; published in the UK by Bodleian Library Publishing on 15 September 2010 and in North America on 15 October 2010; ISBN: 978-1-85124-348-8; pp224; publisher’s UK price £12.99.]