Penny dreadful

Q From Bob Taxin, San Francisco: I was watching an Australian murder mystery on television where a teacher criticised her student’s grotesque theory of what might have happened to the victim by saying that she must have read too many penny dreadfuls. I presume this refers to some sort of horror story, perhaps which sold for a penny. Any thoughts on this?

A They were indeed sold for a penny, a British penny. And they were considered to be dreadful for reasons that will become clear.

It was common in the nineteenth century to publish works in serial form or in magazines — Dickens’s novels, for example, first appeared this way. Such magazines were directed at the educated and affluent reading public and were usually priced at a shilling, unaffordable by the working man.

To meet demand among the less well-off, some publishers brought out serials of inferior technical and literary quality, accompanied by vivid illustrations, which were sold in penny instalments. These featured sensationalist and lurid tales of highwaymen, pirates and murderers as well as exaggerated stories of real-life crimes that were developments of eighteenth-century descriptions of criminals such as the Newgate Calendar. They were most popular among young men, who would sometimes club together to buy single copies which one person might read to others who were illiterate. The genre was widely regarded by the middle classes and by magistrates as a corrupting influence among young people and a cause of the rise in juvenile crime, a view that was contested by others and most famously disputed by G K Chesterton in his essay of 1901, A Defence of Penny Dreadfuls.

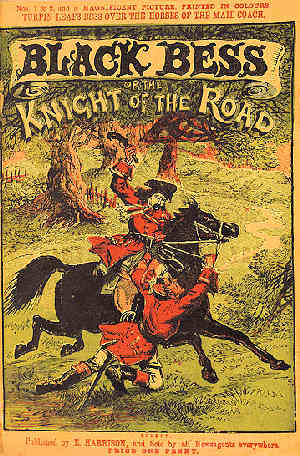

The cover of a penny dreadful of about 1865.

Among better-known examples of the stories were The Maniac Father or the Victim of Seduction, Varney the Vampyre, or the Feast of Blood; Black Bess or the Knight of the Road (stories of Dick Turpin, built on William Harrison Ainsworth’s novel Rookwood of 1834); Ela the Outcast, or The Gipsy of Rosemary Dell; Wagner the Wehr-Wolf; Spring-Heeled Jack, or The Terror of London (a leaping madman who attacked women, a mythical character of the early part of the century); and The String of Pearls (despite its innocuous title this featured the infamous Sweeney Todd, the Demon Barber of Fleet Street).

They started to be called penny dreadfuls around 1860, a term that in its melodramatic and exaggerated disdain adequately communicated the way reputable society thought of them. Similar publications were common in the US — British and American publishers often “borrowed” each other’s material — and came to be called dime novels, a less sensational term that likewise started to appear around 1860. Later, terms such as penny awful and penny blood were used for them in Britain. The latter derives from blood and thunder, unrestrained and violent action or behaviour, a term of the eighteenth century that began to be applied to publications in the 1840s.

In the 1880s, the alliterative shilling shocker — also called a shilling dreadful — began to appear for a type of more substantial short sensational novel, often by writers of some ability (Robert Louis Stevenson’s Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde was placed in this category when it first came out). An early instance was The Dark House, by G Manville Fenn, described in The Pall Mall Gazette on 22 June 1885 as “a ‘shilling dreadful’ of the most hair-stiffening and sanguinary description.” They were often bought for reading during a railway journey, the precursors of today’s airport novels, whodunits and other entertaining genres. These didn’t achieve the same condemnation as the earlier penny dreadfuls, suffering merely from being described in slightly disparaging terms by literary critics as examples of popular culture.

A further development was in the appearance between the two world wars of a set of weekly boys’ magazines published by D C Thomson of Dundee. These were more substantial with a cover price of twopence. They became known as tuppenny bloods (tuppenny being a common contraction for two penny). Together with two other boys’ publications, Magnet and Gem, they were notoriously castigated as a conspiracy against the working classes by George Orwell in his essay of 1940, Boys’ Weeklies. The set comprised Adventure, Wizard, Hotspur, Rover and Skipper; all but the last survived the shortages of the Second World War and one, Rover, lasted until the early 1970s. All eventually succumbed to the appeal of comics, whose illustrations proved more attractive than text-rich stories.