True blue

Q From From Rob Nachum: I am in lexicological heaven for having found your site. Thank you. For random curiosity, I clicked on smithereens. Within the piece is a quote from an Irish Catholic signed as “True Blue”. As an Australian, true blue is equivalent to dinkum or dinky di, meaning honest or genuine. But would it be a stretch to hypothesise that your quoted “True Blue” refers to an Irish-Catholic symbolism that was transported literally and figuratively to Australia by the convicts in the late 1700s to early 1800s? Is to be true blue Australian nothing more than a convict Catholic-Irish relic?

A There are connections between the two usages, but Australian English has much modified the usual British English sense. In Britain (as it has for the past two centuries), the term means a staunch supporter of the Conservative Party, a person of right-wing views. In Canada, it also suggests conservative opinions. In Australia, however, it instead became associated with the working class and the Labor Party and has developed from there.

The link is loyalty.

In medieval Europe blue was the colour of faithfulness or constancy, whose opposite was green. A poem of about 1450, Against Women Unconstant — some claim it was written by Geoffrey Chaucer — criticises an unsteadfast woman for being like a weathercock, that turns its face with every wind; it says, “In stede of blew, thus may ye were al greene.”

True blue starts to be recorded in the 1630s. The story used to be told that the city of Coventry in the English midlands was famous for dyeing a blue that would neither change colour nor fade in washing, and that true blue was coined to indicate a person who would likewise never alter their principles nor their allegiances. We may prefer to think that Coventry had nothing to do with the matter but that true blue was simply an almost inevitable rhyming extension whose meaning was based on the ancient associations of the colour. A proverb, first recorded around 1630, “True blue will never stain”, embodied the ideal of constancy in the figurative stain but that may have been prompted by the blue aprons traditionally worn by butchers in order not to show bloodstains.

Blue began to be associated with politics in Scotland in the seventeenth century through Scottish Presbyterians who formed the Whig party, notably to oppose Charles II being succeeded by his brother James in 1688. Their equivalents in England were the Tories, originally a term for dispossessed Irish people who became outlaws but which became a nickname for English conservatives in the following century (and, of course, is still much used). The 1810 quotation you mention places it in this context.

In Australia, the first meaning was the British one — many letters to newspapers in the nineteenth century advocating conservative views are signed True Blue. (The term was used later in the century for abstainers who joined temperance organisations.) Near the end of the century, it began to be applied to striking workers who were loyal to their comrades and steadfast in resistance. The Advertiser of Adelaide, reporting on 29 September 1890 about a strike of sheep shearers in New South Wales, quoted a telegram that had been sent to the Shearers’ Union: “The men are true blue, and will rather be imprisoned than yield.”

The working-class associations remain (and occur also in blue-collar from the US with a different origin) but from early in the twentieth century true blue, especially in true blue Australian and true-blue Aussie, came also to refer to a quintessential Australian, straightforward, loyal and supportive of his mates.

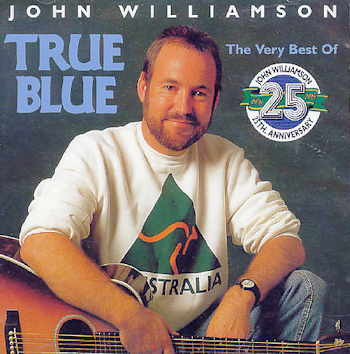

Aussie anthem

These phrases are so widely known that they have become clichés. They have been abbreviated again to true-blue in the same sense as the longer originals to refer to something characteristically Australian (“Christmas in Australia: Howzat for a true-blue celebration”, headlined The Australian in December 2014). It has also borrowed a sense taken from another attribute of a classical Australian — a genuine person or thing (just like dinkum, explicitly equated here in the same newspaper in May 2015: “There’s plenty of support for the true blue, fair dinkum idea”.)

American readers will be poised to tell me that true blue is common in their country, too. It describes a committed supporter of some cause or a loyal fan. In the political sense it’s often applied to the Democrats but a person can also be a true-blue Republican, loyalty being more significant than conventional party colours.