Brown Windsor soup

Subscriber David Procter recently alerted me to a curious culinary and linguistic conundrum.

Brown Windsor is a British soup that rarely appears on menus these days, though chefs such as Jamie Oliver have reinterpreted it for a new generation. Some recent books and foodie websites salute it as a grand old traditional dish which fuelled the nineteenth-century middle classes and sustained the British Empire. This is one:

This hearty soup was both nourishing and popular during the Victorian and Edwardian periods. In fact, Queen Victoria was fond of this soup, and it was often served at royal banquets.

The Unofficial Downton Abbey Cookbook, by Emily Ansara Baines, 2012.

The problem is that nobody has found any mention of brown Windsor soup before this:

After queuing for a quarter of an hour for a seat, he shared a table with a woman whose idea of a suitable four o’clock meal was brown Windsor soup followed by prunes and custard.

The Fancy, by Monica Dickens, 1943.

If it was so significant a dish, why isn’t it in published Victorian menus and why isn’t it mentioned in any cookery book or newspaper of the period?

The name brown Windsor soup may have been a mashup of several other terms. A Windsor soup is known from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and appeared on many menus, one classic recipe requiring chopped beef, veal and bacon. White Windsor soup also existed, a vegetable soup which a recipe of 1911 says was made from white stock, mashed potato and sago. Some writers have used Windsor soup for calves’ feet soup, a food for invalids said to have been served to Queen Victoria in childbed. A few very early recipes for Windsor soup say it should include Windsor beans, presumably the source of the name (despite one claim online, there’s no connection with the British royal family, which changed its name from Saxe-Coburg-Gotha to Windsor only in 1917). In Victorian times dinners might begin with a choice of brown or white soup, so named. The former was a meat soup whose recipes broadly match those of the meat form of Windsor soup.

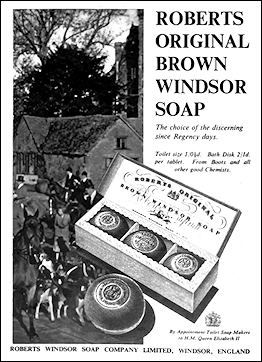

The soap was still being sold in the 1950s.

Another possible constituent of the linguistic melange is the very similarly named brown Windsor soap. Its first appearance was in an advertisement in the Times in 1818 and it seems to have had an excellent reputation. It is said to have been a mixture of olive oil and ox suet, coloured with burnt sugar or umber. It’s possible that people could have unconsciously conflated brown soup and brown Windsor soap.

Alternatively, and more plausibly, the two names might have been put together to make a humorous put-down of an inferior version of brown soup during the austerity of the Second World War.

And I can remember — which of my generation can’t? — the particular culinary horrors of war: Woolton pie, composed of vegetables and sausage meat more crumb than sausage, and brown Windsor soup which tasted of gravy browning. ... Woolton pie and brown Windsor soup featured largely on the menu of the British Restaurants set up under the aegis of the Ministry of Food to provide inexpensive and healthy meals.

Time to be in Earnest, by P D James, 1999. Woolton Pie commemorates Lord Woolton, Minister of Food in 1940.

Whatever its origins, references to brown Windsor soup are common after the Second World War, often in horrified descriptions of the then dreadful state of British cooking in pretentious restaurants and on trains and ferries. It became shorthand for awful food; comics only had to mention it to get a laugh.

But as we’ve seen, in some quarters brown Windsor soup is now held up as an example of excellent nineteenth-century British fare. To explain the change probably needs a culinary expert or a folklorist rather than an etymologist.