Phantasmagoria

In October 1801, a German showman, Paul Philipsthal, placed an advertisement to publicise an event at the Lyceum Theatre in the Strand, London:

The public are respectfully acquainted, that the phantasmagoria, or, Grand Cabinet of Optical and Mechanical Curiosities, exhibiting Magical Illusions, and various other wonderful Pieces of Art, will Open in this Place this day, October 5, and continue every Evening.

The Times (London), 5 October 1801.

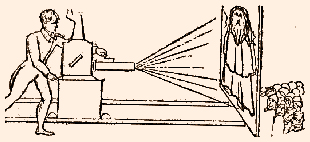

By moving a slide projector (then called a magic lantern) backwards and forwards on rails, figures were made to increase and decrease in size, advance and retreat, dissolve, vanish, and pass into each other. Images were projected on a translucent screen between the audience and the stage, so that they appeared to hang in the air.

A rather crude drawing, supposedly of Paul Philipsthal’s apparatus, from The Portfolio, 1825. Note the wheels and rails for the projector, and the back-projection screen.

A month after his spectacle opened Mr Philipsthal elaborated on it by proclaiming that it would produce “the Phantoms or Apparitions of the dead or absent” and that objects would “freely originate in the air, and unfold themselves under various forms and sizes, such as imagination alone has hitherto painted them”. Much later, a fuller description of the performance appeared:

The head of Dr. Franklin was transformed into a scull; figures which retired with the freshness of life came back in the form of skeletons, and the retiring skeletons returned in the drapery of flesh and blood. The exhibition of these transmutations was followed by spectres, skeletons, and terrific figures; which, instead of receding and vanishing as before, suddenly advanced upon the spectators, becoming larger as they approached them, and finally vanished by appearing to sink into the ground.

Letters on Natural Magic, by David Brewster, 1831. Scull was then rather an old-fashioned spelling of skull.

Philipsthal’s title for his show, Phantasmagoria, was a word he borrowed from fantasmagorie, by then used for some 20 years in French-speaking Europe for similar exhibitions. This derived from fantasme, a phantasm, plus possibly the Greek agora, a place of assembly (though some French dictionaries suggest instead an origin in allégorie, allegory). But as the first edition of the Oxford English Dictionary said, a little sniffily, promoters may have merely wanted “a mouth-filling and startling term” and strict etymology be damned.

He was much bothered by imitators who quickly took advantage of his success, despite his being granted a patent in February 1802, and the popularity of the visual spectacle was so great that the term became a generic one for this type of exhibition. It also entered the language in the modern metaphorical sense of a sequence of real or imaginary images like that seen in a dream.