Etaoin shrdlu

With the idea of speeding up the setting of type, the old Linotype keyboards had their letters arranged in decreasing order of the frequency with which they appear in the language, making the two “home” columns ETAOIN SHRDLU. Operators who made a typing error would often run their fingers down the keyboard to cast nonsense to fill out the line. The resulting cast slug was usually put back in the pot to be melted down and reused, but sometimes, in the heat of composition, the mistake was missed and ended up being printed.

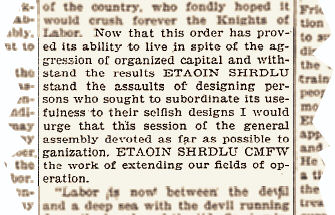

An early appearance, in The Davenport Daily Republican of 1895. Note how the lines containing ETAOIN SHRDLU have been corrected in the ones immediately below. The faulty lines should have been removed before printing.

Each half, and the complete phrase, has occasionally been borrowed to mean something that is nonsense or absurd; the first part is recorded in a story by James Thurber from 1931, and the whole thing appeared in 1942 as the title of a short story by Fredric Brown about a sentient Linotype machine. Jake Loddington has told me about The Naughty Princess by Anthony Armstrong, written in 1945, in which there is a whimsical short story called Etaoin and Shrdlu which ends “And Sir Etaoin and Shrdlu married and lived so happily ever after that whenever you come across Etaoin’s name even today it’s generally followed by Shrdlu’s”. Andrew Stiller mentioned a once-famous play, The Adding Machine, in which Etaoin Shrdlu was a character. The second half of the phrase was used in 1972 by Terry Winograd as the name for an early artificial-intelligence system.

But the sequence was known much earlier among Linotype operators and journalists, as this widely syndicated ode on printing errors testifies:

Some fiendish printer is my secret foe

On the top floor.

He has a trick that fills me up with woe

And oaths galore.

I wrote a sonnet to my lady’s hair

And said that “only with it can compare

etaoin shrdlu cmfwyp vbgkqj xgflflflfl.”

— This made me sore.

Waukesha Freeman, Wisconsin, 23 July 1903.

With computerised typesetting the machines have gone and the associations are almost lost, but the phrase remains a useful mnemonic for the most-used letters in English.