Commash

It’s not every day, even every year, that one learns a new name for a punctuation mark. Nothing seems so inflexible or unalterable in this world, not even the laws of the Medes and the Persians, as the names of these little dots.

And yet, one new to me appeared in the Guardian in April 2008 in a piece about the semicolon, provoked by French reports that it is under threat — in part through a perfidious Anglo-Saxon preference for short sentences. The article included a comment by the novelist Will Self: “Prose has its own musicality, and the more notation the better. I like dashes, double dashes, comashes and double comashes just as much.”

Comashes? A search in books found only a historical reference to an export from the Levant, which may have been a type of stocking or stocking material; a search of the Web was almost as unrewarding but did find a note that a comash is a comma followed by a dash. It was so rare, I wondered if Will Self had invented it. Matters rested there until Frances Peck wrote an article in the Canadian Language Update in March 2010 about it and the interrobang. It turns out that the name is slightly less rare if spelled commash.

This stop was once common in English prose, going back at least to the 1622 First Quarto edition of Shakespeare’s Othello, (“I’le tell you what you should do,— our General’s wife is now the General”). It could appear in pairs to mark a parenthesis (hence double commashes) where we would now use a pair of dashes alone. Its more usual name is comma-dash. In 1949, Eric Partridge wrote in his English, a Course for Human Beings that “The comma-dash, whether single or double, is gradually being discarded.” In the US, the influential Chicago Manual of Style has long since ruled against it.

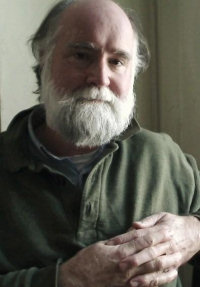

Nicholson Baker

The name commash, plus similar names for a couple of other compound stops, was invented by the American writer Nicholson Baker:

Dr. Parkes ends his brief discussion of “The Mimetic Ambitions of the Novelist and the Exploitation of the Pragmatics of the Written Medium” with Virginia Woolf, so he (pardonably) avoids treating the single most momentous change in twentieth-century punctuation, namely the disappearance of the great dash-hybrids. All three of them — the commash ,—, the semi-commash ;—, and the colash :— (so I name them, because naming makes analysis possible) — are of profound importance to Victorian prose, and all three are now (except for certain revivalist zoo specimens to be mentioned later) extinct.

Survival of the Fittest, by Nicholson Baker, first published in the New York Review of Books, 4 Nov. 1993; reprinted under the title The History of Punctuation in his collection of essays The Size of Thoughts, 1996.

Of the three, the colash or colon-dash has survived best by far, frequently being used to introduce a list. The others are verging on historical relics. So, alas, are Nicholson Baker’s terms for them.