Fewmet

“The fewmets have hit the windmill,” cried a character in Harvard Lampoon’s parody Bored of the Rings. Readers not familiar with archaic English hunting terms will have missed the joke.

Fewmets — also called fewmishings — are the excrement or droppings of an animal hunted for game, especially the hart, an adult male deer. For medieval hunters they were evidence that an animal was nearby; their condition gave a clue as to how near the quarry actually was. Huntsmen would bring fewmets to their masters to demonstrate that game was there to be chased and that the hunt wasn’t likely to be a waste of time.

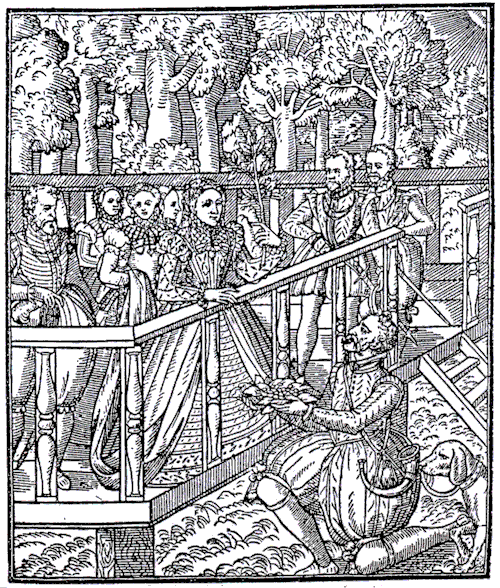

A huntsman showing fewmets to Queen Elizabeth I. From The Noble Arte of Venerie or Hunting, by George Gascoigne, 1575.

To make a proper assessment, the huntsman needed to know a lot about the ways of the animal:

You muste vnderstand that there is difference betweene the fewmet of the morning and that of the euenyng, bicause the fewmishings which an Harte maketh when he goeth to relief at night, are better disgested and moyster, than those which he maketh in the morning, bycause the Harte hath taken his rest all the day, and hath had time and ease to make perfect disgestion and fewmet, whereas contrarily it is seene in the fewmishyng whiche is made in the morning, bycause of the exercise without rest whiche he made in the night to go seeke his feede.

The Noble Arte of Venerie or Hunting, by George Gascoigne, 1575.

The word came into English during the fourteenth century and is from an Anglo-Norman French variant of Old French fumées, droppings.

With the decline in great landed estates and the hunting they offered, the word went into a decline, to become fashionable again in recent decades with the rise in fantasy fiction and role-playing games. The inspiration for most of the modern examples must surely be this:

“I know what fewmets are,” said the boy with interest. “They are the droppings of the beast pursued. The harbourer keeps them in his horn, to show to his master, and can tell by them whether it is a warrantable beast or otherwise, and what state it is in.”

“Intelligent child,” remarked the King. “Very. Now I carry fewmets about with me practically all the time.”

“Insanitary habit,” he added, beginning to look dejected, “and quite pointless. Only one Questing Beast, you know, so there can’t be any question whether she is warrantable or not.”

The Once and Future King, by T H White, 1939.

In the exotic spirit of King Pellinore’s questing beast, these days the animal producing the fewmets is more frequently a dragon:

He’s going to where my dragons were! Come on, Meg, maybe he’s found fewmets!” She hurried after boy and dog. “How would you know a dragon dropping? Fewmets probably look like bigger and better cow pies.”

A Wind in the Door, by Madeline L’Engle, 1973.

It has become a useful substitute in such literature for a couple of coarser words: “‘Oh, fewmets,’ Schmendrick cursed” (James A Owen, The Dragons of Winter); “Speaking between friends and meaning no offense, you’re full of fewmets.” (Poul Anderson, Satan’s World); “Caryo intends to be caught, so she can kick the fewmets out of him” (Mercedes Lackey, Exile’s Valour).

The word has also been spelled fumet, which might lead to an unfortunate confusion with the concentrated fish stock used for seasoning that goes by that name, a relative of the Roman garum. The source of this sense of fumet is a related French word, originally applied to the smell of game after it had hung for a while.