Whiff-waff

Alexander Boris de Pfeffel Johnson, Mayor of London, had a good 2012 Olympics. He was in the news almost every day through popping up in bumbling good humour in the media and at many events. Even his being stuck on a zip-wire 15ft above the ground on the banks of the Thames for several minutes, which would have been a humiliating catastrophe for most politicians, was salvaged by his banter with the watching audience.

Another frequent reference to him in news reports in the past two weeks has been to his speech at a party to mark the handover of the Olympic flag at the end of the 2008 Beijing Olympics. He declaimed, “Ping-pong was invented on the dining tables of England, ladies and gentlemen, in the 19th century. [CHEERS] It was, and it was called whiff-whaff.” Experts jumped on him at the time, telling him he’d got his facts wrong. Chuck Hoey, Curator of the International Table Tennis Federation’s Museum in Lausanne, wrote a heavily illustrated article setting out all the facts, which he entitled Boris Johnson and the Whiff-Waff Gaffe.

Yes, Whiff-Waff. No second h. Every journalist who has written of Whiff-Whaff in recent weeks has spelled it wrong (including those on 28 July who reported the claim by the French ambassador to London, Bernard Emié, that table tennis was invented in France, which led to a furious rebuttal by Johnson). We probably can’t blame Boris for the way the Beijing reports were spelled, as his comments were on TV and reporters naturally wrote it the way it sounded through the overwhelming influence of standard word reduplication. However, Boris did use the whiff-whaff spelling in his book Johnson’s Life of London of 2011. There’s nothing new in the error — every reference I’ve found on both sides of the Atlantic going back to the 1930s has included both hs.

An original boxed set of Whiff-Waff

Mr Hoey explained that Whiff-Waff was actually a latecomer to the game, being registered as a trademark by the British manufacturer Slazenger on 31 December 1900. I have failed to find contemporary newspaper references to the product or even advertisements for it, so we must assume that it wasn’t hugely successful. The name survived better in the US than in the UK, which is perhaps why one French website suggests that it was an American invention. Unlike Whiff-Waff, the name of the competitor trademarked by Hamley Brothers of London four months earlier has entered the language: Ping-Pong. An onomatopoeic allusion to the sound of ball on bat and table, the name seems to have been known earlier to describe an improvised indoor version of lawn tennis (in tradition, played by bored army officers using balls made from champagne corks and bats fashioned from cigar box lids).

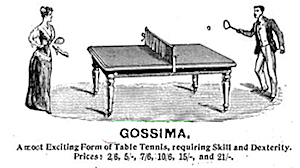

Gossima was just one of the games being promoted by Jaques and Son for Christmas 1898. This advertisement appeared in The Graphic on 10 December that year.

Gossima was just one of the games being promoted by Jaques and Son for Christmas 1898. This advertisement appeared in The Graphic on 10 December that year.

Jaques and Son, also of London, brought out Gossima in 1891, which had some success, though a decade later it was incorporated into Ping-Pong, being sold for a while under both names. The true creator of the game, Mr Hoey explained, was the unsung David Foster, who patented a version in 1890 but had no commercial success with it.

Incidentally, the name now standard for the game, table tennis, is recorded from the late 1880s for a number of games, including one whose description reads like a cross between tabletop lawn tennis and billiards (using cues, not bats), and one that was in essence tiddlywinks. But when Gossima was noted in The Graphic on 3 December 1892, it was described as “a new table-tennis game”, which showed that the word had by then become known to mean something near its modern sense — illustrations show Gossima was essentially the game we now know.

The one unexplained issue is why Slazenger should have come up with such an odd name as Whiff-Waff. The Ogden Standard-Examiner of Utah reported in 1966 that the US Table Tennis Association had said it was because of the knitted web ball it used. (Before celluloid ones were introduced in 1901, players had used rubber balls or cork balls covered with a net.) That may explain the whiff (a slight gust of wind) but not the waff, though that’s a Scottish word meaning a waving movement, as of the hand, a relative of waft. It’s just as likely (that is, not very) that it’s from the English dialect term, whiff-whaff, known also in the US at the time, meaning trifling words or actions. That really would put the game in perspective.