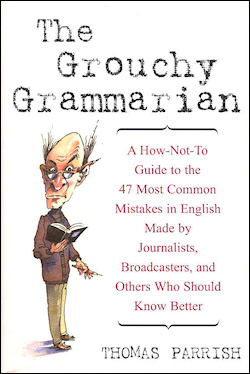

The Grouchy Grammarian

If the title isn’t enough to give you the idea, the wordy subtitle certainly will: “A How-Not-To Guide to the 47 Most Common Mistakes in English Made by Journalists, Broadcasters, and Others Who Should Know Better”.

Though humorously written and very readable, Thomas Parrish’s book seems at times to consist of an extended catalogue of the errors of writing and speech that have offended the author (or, to accept the book’s conceit, his alter ego, the eponymous Grouchy Grammarian).

He has rounded up the usual suspects: confusion between it’s and its, among and between, and may and might; between lie and lay, and homophone pairs such as lead and led. He illustrates dreadful things that people do with apostrophes, problems with subject and verb agreement, the misuse of former, the incorrect use of whom, dangling participles, malapropisms, and more.

As his subtitle makes clear, his examples are mostly taken from the media, which I feel sometimes shines the spotlight too brightly on errors made by broadcasters and journalists. Theirs is a stressful occupation with constantly looming deadlines in which it is all too easy to make a slip that cannot be recalled and corrected. Mr Parrish would, I suspect, argue that a more thorough knowledge of the basics would prevent the most egregious errors. Perhaps so.

I disagree with a few things: straight and narrow is not just a mistake for strait and narrow but is of independent formation with a respectable ancestry (I’ve found examples going back into the 1840s); chaise lounge, though a folk etymology for the correct French chaise longue, is now too well established in the US for a book on style to claim it as an error (it is, for example, included in several current American dictionaries without comment); ice tea for iced tea is not simply an error but a well-established regional form that parallels ice cream (nineteenth-century prescriptivists were equally hard on this, arguing similarly that it ought to be iced cream); cut and dry isn’t necessarily a mistaken form of cut and dried but a variant that’s known from the eighteenth century (Swift used it in 1730, for example).

But Thomas Parrish is no knee-jerk pedant. He is happy to dismiss the old canard that none must always take a singular verb; he is relaxed about the use of like to mean as (though not the intrusive like that generates a meaningless sentence break in so many conversations); he’s very aware that language is not static. His greatest concern is that whatever we write, we should say clearly what we mean to say. This is summed up by his opening section, which urges all writers to “Think!” — not, as the late Thomas J Watson of IBM meant it, to exercise the little grey cells in the direction of innovation and invention, but just to stop a moment and reflect on what it is one is actually trying to communicate.

My largest concern about his efforts is that I’m not at all sure what audience he is writing for. Most people who ought to read it probably won’t, or realise that they need to. It will be picked up by some who know that their English could be improved (perhaps even by some in the media), but I suspect that a sizeable proportion of its readers will know most of the answers already and will read it largely to have their prejudices about the degraded state of media English confirmed.

[Thomas Parrish, The Grouchy Grammarian, published by Wiley in October 2002; ISBN 0-471-22383-2; hardback, pp186; publisher’s price US$19.95.]