Snake oil

Q From Sam Foreman, Pittsburgh: I think just about everyone knows that a snake oil salesman is a huckster trying to sell some product of dubious quality. I wonder where snake oil came from, given that it seems there could be many other descriptive metaphors applied, and if this witty term has an identifiable creator. I also wonder and whether it preceded the age of films or might have been a result of depictions in it.

A It’s worth recounting the history of the term snake oil in some detail since accounts available online and in many books don’t match the evidence in historical sources.

We may dismiss out of hand the assertion in several places that the name snake oil is a corruption of seneca oil. This was the name given to crude petroleum that seeped from the ground in Pennsylvania and New York State and which was sold in the early nineteenth century for medicinal purposes under that name and also as Indian spring oil.

Snake oil actually derives from the folk belief in North America that rattlesnake oil was a remedy for problems such as rheumatism and croup. This is the first mention of the oil that seems to exist:

There are three Sorts of Oils in that Country [Virginia], whose Virtues, if fully proved, might not perhaps be found despicable. The Oil of Drums, the Oil of Rattle Snakes, and the Oil of Turkey Bustards.

Letter from the Reverend John Clayton, 1687, reproduced in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society in 1739. Clayton later became Dean of Kildare in Ireland and was the first person to extract an inflammable gas from coal. The oil of drums comes from one of several North American fish called more fully drum-fish that can make a drumming noise, presumably in this case the salt-water drum of the Atlantic coast. Thanks to Hugo van Kemenade for unearthing this.

A much later example suggests a particular medicinal purpose for the oil:

There is one article more, which, as some people deem it a specific in the croup, it may not be improper to mention, which is ... rattle-snake’s oil, as it is called.

A Dissertation on Cynanche Trachealis, or Croup, by Abraham Haskell, read before the annual meeting of the Massachusetts Medical Society, 1812. Dr Haskell goes on to mention its extremely fishy and nauseous taste.

Similar beliefs have been widespread, but especially in traditional Chinese medicine, in which oil of the Chinese sea snake (Laticauda semifasciata) is used to treat arthritis and other joint pains (the oil has recently been found to contain high levels of omega-3 fatty acids, which can reduce inflammation, among other benefits). Some writers say snake oil and beliefs about its value were brought to the US from the late 1840s by the Chinese immigrants who helped build its railways, though the evidence is clear that Americans had much earlier been using rattlesnake oil for similar purposes. Others hold that the beliefs derive from the practices of native Americans that were borrowed by immigrant settlers.

The evidence suggests that they actually derive from an earlier belief in Britain that preparations such as viper oil, viper wine and viper jelly, based on the viper or adder, our only venomous snake, would cure various ills. For example, there are two detailed recipes in a book by Sir Thomas Ruthven of 1654, The Ladies Cabinet Enlarged and Opened, one of them described as a quintessence of adder that is claimed to be

of extraordinary virtue to purify the blood, flesh and skin, and consequently all diseases therein. It cures the falling sickness, strengthens the brain, sight and hearing, and preserveth from gray hairs, reneweth youth, preserveth women from abortion, cureth the gout, consumption, causeth sweat, is very good in and against pestilential infections.

Advertisements in US newspapers from the 1840s offer rattlesnake oil for sale but editorial references are rare before the 1880s. Some from that decade lament the decline in production of snake oil as a rural craft, a small-scale seasonal occupation among countrymen, in the north Pennsylvania mountains and the Ozarks in particular. Hunters would go out in the early autumn to catch snakes and “try” them — boil them to extract the oil, as whalers did with blubber — or behead them and hang them in the sun to drain. Later reports imply the craft was being industrialised, at least to some small extent, with snake farms being set up to breed them and sell them on to businesses that extracted and sold the oil. Though the snake oil remedy was useless, these reports suggest that it was a legitimate trade that provided the genuine article to customers who retained their belief in it.

Some people still hold to curious old superstitions concerning the curative properties of the oils of certain animals; and to hear the druggists tell of the strange articles called for by some of their customers is to be reminded of the vagaries indulged in by the aboriginal medicine man in his native wigwam. For instance, there are persons who pin great faith still to the virtues of rattlesnake oil, and who believe it is a specific for rheumatic afflictions.

Daily Globe (St Paul, Minnesota), 7 Jun. 1882.

This belief provided an opening to hucksters selling products that had never been near a snake. Some replaced rattlesnake oil with oil from creatures such as raccoon, woodchuck, skunk or bear. Others concocted a product from whatever was serviceable and cheap with no concern for any medical effects, good or bad.

This is an early description of an itinerant mountebank of this type, one who later became a cliché in westerns:

The scoff and jeer of the multitude turn from him as water from the shining back of a duck. He always comes up on top, beaming his perpetual smile, and asks who will have the next bottle of ready-relief, pain-killer or rattle-snake oil. The facility and rapidity of his speech is phenomenal, and his fund of Billingsgate inexhaustible. ... [T]he traveling quack ... may be of some use in the world, but like that of the fly and mosquito it is not easy to say just in what it consists. Apparently his success is based upon his enormous development of cheek, in connection with that fixed element in human nature, gullibility.

Hagerstown Herald and Torch Light (Maryland), 14 Jul. 1880. Billingsgate refers to the London fish market, whose porters were renowned for their invective and bad language.

A development was the travelling medicine show, in which a variety of entertainments sugared the hard sell of the proprietor’s nostrums for curing every kind of ailment. They became common enough to be unremarkable by the late nineteenth century and continued well into the twentieth despite attempts to outlaw them. From the 1890s, their rise was matched by the growth of print advertisements for what were mistakenly called patent medicines: none were ever really patented, because their makers would have had to list their ingredients. There was a huge variety, those touted as snake oil being a significant minority, but ones with seemingly miraculous powers. In their claims of universal efficacy some are as comprehensive of those in the 1654 British book.

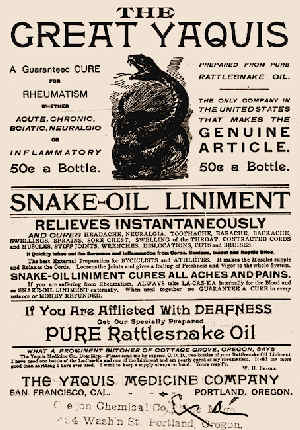

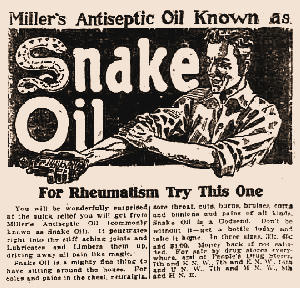

Two commercial advertisements for snake oil, above from 1903 and below from 1918.

An advertisement of 1891 urged readers to “Try one of Dr. Miles Rattle’s Snake Oil Pain Cure Plasters, the most powerful remedy for external application”. Another in Portland in 1903 stated that the Great Yaquis Snake Oil Liniment “relieves instantaneously and cures headaches, neuralgia, toothache, earache, backache, swellings, sprains, sore chest, swelling of the throat, contracted cords and muscles, stiff joints, wrenches, dislocations, cuts and bruises.” The proprietor of Dr Reese’s Snake Oil Liniment in later years was much more succinct, claiming simply that it would “cure any pain, external or internal”. Another for Miller’s Antiseptic Oil in 1918, also known as Snake Oil, argued that “Snake Oil is a mighty fine thing to have sitting around the house. For colds and pains in the chest, neuralgia, sore throat, cuts, burns, bruises, corns and bunions and pains of all kinds, Snake Oil is a Godsend.”

We can’t say now whether any these products actually contained any rattlesnake oil. Most surely didn’t. One denunciator wrote of

the damnable curse of street fakirs, charlatans, and patent-medicine venders [who] reap dollars from the sale of snake oil, made of rot-gut whisky, a little ammonia and tincture of iron.

The Western Druggist, Jul. 1895. Vender is an old spelling of vendor. It may be relevant that snake oil at about this time came to have a slang sense of low-grade whisky.

One notable example — Clark Stanley’s Snake Oil — was analysed in 1915 and in the analyst’s words was found to consist “principally of a light mineral oil (petroleum product) mixed with about 1 per cent of fatty oil (probably beef fat), capsicum, and possibly a trace of camphor and turpentine.”

It was findings like this following the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 that led to the term snake oil appearing in print in the 1920s as a symbol of fraud, although it had been understood for decades by informed people that any hawker of something so called was almost certainly a quack and his product a swindle.

The now-common term snake oil salesman was a little slower to appear: the first recorded use I can find is dated 1933.