Hootenanny

Q From Steven Hancock: How did hootenanny arise?

A This is an example of a rule I deduced from extensive experience many years ago: that the shortest questions are the most trouble to answer. The quick reply is that we don’t know the whole story. But its history is curious and worth exploring.

Hootenanny is a successful American linguistic export. Many people throughout the English-speaking world are familiar with it as a term for what one dictionary on my shelves describes as “an informal gathering with folk music”. So it’s a pity we have no clear idea of its ultimate origin. (The idea that it refers to the figurative offspring of an owl and a female goat may be disregarded, even though in its early days it was written at times as hootnanny.)

The indications are that in a directly musical sense it arose about 1940. The first examples are from a short-lived left-wing newspaper in Seattle, which ran regular fund-raising musical events:

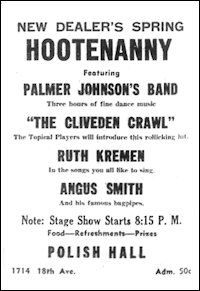

The New Dealer’s Midsummer Hootenanny. You Might Even Be Surprised! ... Dancing, Refreshments, Door Prizes.

An advertisement in the Washington New Dealer, 5 Jul. 1940, quoted in the Oxford English Dictionary. Another advert in the paper, from March 1942 (below right), lists dance music, singing and bagpipes as part of the event.

Despite this, the message from various archives is that it didn’t really begin to catch hold until the middle 1940s. The early examples, like the one above, referred to entertainments with no folk music content. Its link to folk evolved during the 1950s, with Pete Seeger often being linked to the shift. In his book The Incompleat Folksinger, published in 1972. Seeger says he encountered the word when he and Woody Guthrie played at a New Dealer fund-raiser and recalled that the name won out by a nose over another word for an unidentified thingy, wingding. Seeger says he started to use hootenanny for informal folk evenings in people’s homes. So there is a direct line of descent from the sense of an unspecified object through the New Dealer’s choice of name via Seeger to the wider folk-music community. The connection was strengthened by the US television programme Hootenanny in the early 1960s. It had reached the UK a little earlier, by the late 1950s:

All over the British Isles today at ceilidhes, hootennanys and similar gatherings in pubs, clubs and private houses, folk music is flourishing as it has not done for over a century.

The Times, 10 Jan. 1959.

However ... in various spellings the word was around both earlier and later as one of those incoherent terms for a thing whose real name is unknown or momentarily forgotten. As an example, American newspapers ran a syndicated piece in the late 1930s about a man trying to teach his wife to drive. This extract gives its flavour:

When it starts you push down on the doo-funny with your left foot, and yank the uptididdy back, then let up the foot dingus and put your other foot on the hickey-ma-doodle, don’t forget to push down on the hootananny every time you move the whatyoumaycallit and you’ll be hunkydory. Gosh, dear, what’s the matter, haven’t you been listening to me?

Centralia Daily Chronicle, 10 Jul. 1937.

In the journal Western Folklore in 1963 the American researcher Peter Tamony argued it should be classed as “an indefinite American word” that meant what you wanted it to mean. There’s no shortage of ways it was applied. It could be a device to hold a cross-cut saw in place while sawing a log. The lexicographer Jonathon Green found a reference to it in a newspaper of February 1918 in Lincoln, Nebraska, as a slang term of US soldiers for cooties (body lice). Subscriber Philip Miller was told by an elderly lady in southern Michigan in the early 1970s that in her youth, around the First World War, rural people used the word for a food mill. A play by J C McMullen of 1920, Turning the Trick, includes the lines “‘Have you any visitors at present?’ ‘No one. Wait a minute though. I forgot that bolshevik hootenanny Kathleen’s brought in’”; the young woman so described is rebellious (one sense of Bolshevik at the time, abbreviated to the British bolshie) as well as wild and unconventional and is seen as a bad influence. Another sense, of an ignorant or stupid person or clod, is recorded from about the same period in rural Ohio.

The form hootin’ nanny appears in newspapers from 1919 onwards as a slang term for a motor car. I’ve found that it referred also to other varieties of noise-making machines, including a railway locomotive and a home-made musical instrument. Other sources claim hootin’ nanny was earlier a southern US dialect term for a slatternly or talkative woman. In October 1929 the Evening News Journal of Clovis, New Mexico, mentions a visit by a sextet called Hooten-Anny at which “harmonious selections were sung”. Was the name a self-deprecating play on hootin’ nanny? It seems highly probable that this version of hootananny, whatever it first meant, came directly from hoot for a discordant noise. It may even have been the original from which the New Dealer’s musical sense evolved.

There are other early music references. In January 1924, an advert in the Evening Gazette of Xenia, Ohio, told its readers that “Marion McKay and his Greystone Orchestra have recorded Hootenanny and Little Butterfly for Gennett Records”. A report in the Newark Daily Advocate in April 1921 noted that “the comedy sketch, ‘The King of the Hootananny’ written by Robert Abernathy and featuring several original songs, was the hit of the evening at every concert.”

Altogether, this is a classic tale of a folk word that shifted sense and became widely known through a series of accidental happenings.