Boot and trunk

Q From Brock Lupton: Why is the rear storage compartment of a car (trunk in North American parlance) in British usage called a boot?

A Boot is an excellent example of linguistic conservatism.

I’ve mentioned this before with dashboard and with carriage, the usual British term for one car of a railway train. The latter word is a relic of stagecoaches, since early passenger accommodation for trains was built by the same men who constructed horse-drawn carriages and coaches and the name stuck.

A tiny detail from Joris Hoefnagel’s 1568 painting of Nonsuch Palace in Surrey. You can just see one servant in the coach sitting sideways in a boot.

We’re in the same area with boot. Around 1600 it began to be used for an uncovered projecting seat outside the doors on each side of a coach in which passengers sat facing sideways to the direction of travel. It’s often said that these seats were for servants but this seems not always to have been the case. On 23 August 1667, Samuel Pepys, Clerk to the Navy Board in London, recorded in his diary an accident with a coach in which he was travelling with Sir William Penn, one of the commissioners of the Board (and father of the founder of Pennsylvania): “We were forced to leap out — he out of one, and I out of the other boote”.

Earlier in the century, John Taylor, the water-poet of London, heartedly disliked the then new-fangled hackney coaches because they took trade away from him and his fellow watermen on the Thames:

It [the coach] wears two boots, and no spars; sometimes having two pairs of legs in one boot: and oftentimes against nature most preposterously, it makes fair ladies wear the boot. ... Moreover, it makes people imitate sea-crabs, in being drawn sideways; as they are when they sit in the boot of the coach.

The World Runnes on Wheeles, by John Taylor, 1623.

By the beginning of the nineteenth century, the boots had been moved to the ends of coaches and had turned into storage areas. One was under the coachman’s seat at the front, the other under that of the guard at the back.

So much for the history of the contrivance. The origin of its name is a lot harder to work out, though the experts usually say it’s the same word as the one for a type of footwear. It has been suggested that it’s from French boîte, a box, though that wasn’t its function when it was named. Another theory is that the early seats were in the rough shape of boots, though I detect the influence of folk etymology. The best-known exponent of this suggestion was Sir Walter Scott:

The insides [inside passengers] were their graces in person, two maids of honour, two children, a chaplain stuffed into a sort of lateral recess, formed by a projection at the door of the vehicle, and called, from its appearance, the boot, and an equerry to his Grace ensconced in the corresponding convenience on the opposite side.

Old Mortality, by Sir Walter Scott, 1816.

The vocabulary of horse-drawn vehicles was the same on both sides of the Atlantic, as it was old enough to have been in the speech of early colonists. The storage spaces continued to have the same name in both the UK and the US until the end of the coaching era:

As Bill opened the double-locked box in the “boot” of the coach — sacred to Wells, Fargo & Co.’s Express and the Overland Company's treasures — Mr. Wiles perceived a small, black morocco portmanteau among the parcels.

The Story of a Mine, by Bret Harte, 1877.

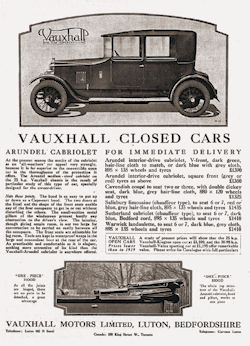

Above: A 1932 Chrysler 8, showing its external trunk (photo courtesy of John Lee). Below: An advertisement in the Illustrated London News in 1922 for a Vauxhall car with integral boot.

Unlike coaches, storage on many early motor vehicles was regarded as an extra, not part of the structure of the vehicle. The rear passenger seats were usually placed over the back wheels with no room for luggage behind them. Particularly in the US, providing storage was the job of the owner, who often fitted luggage racks at the rear of the vehicle or on the running boards. In American publications from 1907 we start to see references to automobile trunks. These were essentially old-fashioned steamer or travelling trunks that were packed indoors and brought out to be fixed to the vehicle’s luggage rack by leather straps. Typical of the period was this mention:

Outside, Cargan heard a burst of merry voices and saw Waldron hurried away by two laughing girls to an automobile waiting with a trunk strapped behind it.

Atlantic Narratives, 1918.

It wasn’t until the 1930s that storage spaces commonly began to appear as integral parts of American vehicles. For example, Chrysler and Buick continued to provide rear racks for trunks well into that decade. In 1930 the US magazine Automobile Topics noted integral trunks as newsworthy: “Rear-end trunks were larger and more prevalent. In one line of cars they were designed into the rear of the body itself.” Manufacturers and users borrowed trunk from the earlier external arrangements because, by the time they needed a word for them, knowledge of the stagecoach term had passed from most people’s minds

British experience was much the same in the early days. Some makers, such as Rolls-Royce, took a similar approach and fitted luggage racks and trunks. However, others began to provide internal luggage space, and did so rather earlier than in the US. This meant that the old coaching term was still in people’s minds in Britain and was adopted by car builders and owners. The first known reference to a car boot, so called, was in the magazine Autocar in 1908; by the early 1920s makers such as Vauxhall were advertising vehicles with them.