Bob’s-a-dying

Q From Les Kirkham: I know this phrase is used in the navy to mean “drunk”, even “raucously drunk”, often as “kicking up Bob’s a-dying”, but what are its origins? Is it anything to do with Bob’s your uncle?

A The usual dictionary sense of Bob’s-a-dying is of a disturbance or uproar, perhaps with physical violence involved. It requires no stretch of imagination to connect this with sailors on shore leave getting well tanked up, but drunkenness as such doesn’t seem to be the idea behind it.

It’s rare these days and most people will probably have come across it only in such works as the seafaring novels of Patrick O’Brian. He uses it five times in various books, as here about his crew:

Once ashore they kicked up Bob’s a-dying to a most shocking extent and then set about the soldiery.

Blue at the Mizzen, by Patrick O’Brian, 1999.

The dating of the expression fits the Napoleonic period in which the books are set. We begin to see it in print in 1828 but may reasonably assume it’s at least a decade or two older. It’s much too old and too different in sense to be linkable to Bob’s your uncle, though it may be added to the list of sayings involving somebody or something named bob that may just possibly have been an influence.

By the end of the nineteenth century it had largely dropped out of public writings but was being recorded in dialect, from Cornwall to Northumberland, sometimes in modified forms such as bobs-a-dial or bobs-a-dilo. It was said to mean “boisterous merriment”, though it could also mean causing a row or making a huge fuss. Thomas Hardy has a character in Under the Greenwood Tree say, “You see her first husband was a young man, who let her go too far; in fact, she used to kick up Bob’s-a-dying at the least thing in the world.”

When it first appeared, people seemed clear enough what it was referring to. A story in the Metropolitan Magazine in 1835 has “I could dance a hornpipe and kick up Bob’s a-dying.” Two years earlier a short story appeared that described setting sail on a warship:

Man the haulyards — let go reef-tackles, cluelines, buntlines — light up in the top — hoist away! Up they went to the tune of “Bob’s a dying”.

The Monthly Magazine, Feb. 1833.

If any doubt should remain, let me dispel it with this later example:

The bridal party marched in regular order next, and over them a parasol, attached to a long rod of iron, was carried by another man, and by his side was an accordeon player, striking up some lively strains, such as “Pop goes the Weasel,” “Bob’s a dying,” &c.

Nottinghamshire Guardian, 29 June 1854. Accordeon was a contemporary spelling of accordion, derived from its original German name.

Patrick O’Brian was also sure of its musical origin:

He too had danced to the fiddle and fife, his upper half grave and still, his lower flying — heel and toe, the double harman, the cut-and-come-again, the Kentish knock, the Bob’s a-dying and its variations in quick succession and (if the weather was reasonably calm) in perfect time.

The Ionian Mission, by Patrick O’Brian, 1981.

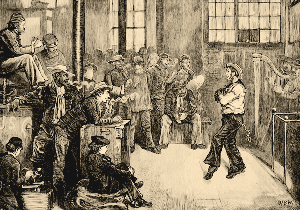

A sailor dancing at a seaman’s refuge in London’s East End. From the Illustrated London News of 20 December 1873.

The many references to kicking up Bob’s a dying suggests a high-kicking dance. This presumably wasn’t a sea shanty but a tune particularly popular with seafarers. It’s a pity that this doesn’t now seem to be known. It must have been particularly lively to have become linked to uproar ashore, though sailors putting the boot in during an affray would at once have seen the connection.

Who or what was bob is likewise not known. One theory has it that it referred to a shilling in old British currency, known as a bob since the latter part of the eighteenth century; bob might have been dying because the sailor’s money was almost spent. On drink, we may reasonably suspect.