Spiv

Q From Richard English: I have just been discussing with my son the origin of the word spiv. I am well aware of the meaning of the word — my late uncle Arthur English made his living depicting a loveable spiv in the 1940s and early 1950s — but until now I have never even thought about the origin of the word. My son, who is studying early 20th century history, claims that he had seen a suggestion that it was back-slang derived from VIPs but I thought that this acronym was more recent than WW2. In any case, I couldn’t see that a spiv was necessarily the opposite of a Very Important Person; indeed, I suspect that a spiv was a VIP to many customers during the war and just afterwards.

A Let’s put the footnotes first on this one, because spiv is a British English colloquial term whose meaning and cultural implications may be obscure to anyone outside the country.

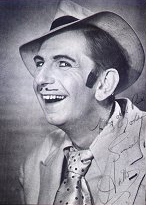

The late Arthur English

in his role as a spiv.

A spiv was typically a flashily dressed man (velvet collars and lurid kipper ties) who made a living by various disreputable dealings, existing by his wits rather than holding down any job, and who often supported himself by petty black-market dealings. (Another name was wide boy, with wide having the old slang sense of sharp-witted, or skilled in sharp practice.) He was small-time, living on the fringes of real criminality. He is most closely associated with the Second World War and after in Britain; he always seemed able to get those coveted luxury items that were unobtainable during that period of austerity except on the black market, such as nylons. As well as your uncle, still fondly remembered, Private Walker in the BBC television series Dad’s Army was a typical spiv; Arthur Daly, the second-hand car dealer in Minder, was a linear descendent of the breed.

Until recently, we have had no idea where the name comes from, which has given rise to a lot of uninformed speculation. It has indeed been said that it is VIPs backwards; also that it was a police acronym for Suspected Persons and Itinerant Vagrants. VIP does date from the same period, but it would be very surprising if it were the source. Apart from the sense being wrong, inverted acronyms based on word play were uncommon then. The police story is a well-meaning attempt at making sense of the matter.

An early appearance in print was in School for Scoundrels in 1934: “Spiv, petty crook who will turn his hand to anything so long as it does not involve honest work”. As a result of investigation in 2007 by a BBC television programme, Balderdash & Piffle, we have learned that the word was around earlier. Its first appearance in print is now known to be in a book of 1929, The Crooks of the Underworld, written under the pseudonym of C G Gordon; this included a reference to “a clique of Manchester ‘spives’”. We also have a better idea of the historical background to the term. The activities of an unsuccessful petty crook named Henry Bagster, a London newspaper seller and petty criminal of the early years of the early twentieth century, were widely reported at the time. Bagster’s court appearances for theft, selling counterfeit goods, assault, and loitering with intent to commit a felony were recorded in the British national press between 1903 and 1906. His nickname was “Spiv” recorded from 1904.

We don't know why he was given that nickname, though it may indicate that the slang term was in use even then. The word itself may well have come from the dialect term spiving, smart, or spiff, a well-dressed man. This developed into the adjective spiffy, smart or spruce, recorded from the 1850s, and also into spiffed up, smartly dressed. In The Cassell Dictionary of Slang, Jonathon Green instead suggests the Romany spiv, a sparrow, which was used by gypsies, he says “as a derogatory reference to those who existed by picking up the leavings of their betters, criminal or legitimate”.