Not my pigeon

Q From Helen Mosback: I have just read a serialised version of John Rowland’s Calamity in Kent. It includes this: “In fact, it’s your pigeon, as they say in the civil service.” I was wondering if you could shed any light on the expression it’s your pigeon? I have to admit to being quite taken by the Polish expression not my circus, not my monkeys to indicate that something is not one’s problem, and would be very happy should I have found an equally enchanting English expression!

A Readers may not be familiar with John Rowland, a little-known and neglected British detective-story writer who published Calamity in Kent in 1950. The British Library has republished it this year in its Crime Classics series.

The date of his book is significant, since at that time the expression was more familiar to people in the countries of what is now the Commonwealth than it is now. It had come into the language around the end of the nineteenth century.

The idiom suggests something is the speaker’s interest, concern, area of expertise or responsibility. This is a recent British example:

If posh people aren’t your pigeon, the correspondence on display in this book will be a massive bore and irritation.

The Times, 8 Oct. 2016.

It also turns up in the negative in phrases such as “that’s not my pigeon”, denying involvement or responsibility in some matter.

Despite your analogy with the Polish expression, the pigeon here isn’t the animal. It’s a variant form of pidgin. The name is said to derive from a Chinese attempt to say the word business; the original pidgin, Pidgin English, was a trade jargon that arose from the seventeenth century onwards between British and Chinese merchants in ports such as Canton. The word pidgin is recorded from the 1840s and has become the usual linguistic term for any simplified contact language that allows groups that don’t have a language in common to communicate.

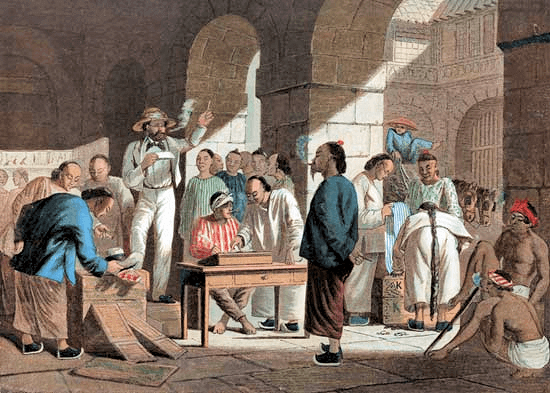

English traders selling goods in Guangzhou (Canton), China, 1858.

This is an early example of pidgin being used in the figurative sense:

We agreed that if anything went wrong with the pony after, it was not to be my “pidgin.”

The North-China Herald (Shanghai), 1 Aug. 1890.

Most early examples in English writing were spelled that way, though by the 1920s the pigeon form was being used by people who didn’t make the connection with the trade language.