Lame duck

Q From James Macdonald: During Barack Obama’s recent visit to London, some British newspapers referred to him as a lame duck president. That expression is familiar to me, of course, but I did wonder why somebody who was ineffectual or unsuccessful should be described in that strange way. Lame I can understand, but why duck?

A Lame ducks, of course, can be incompetent or ineffectual firms or governments as well as individuals — British political life has seen many examples of both described as lame ducks down the decades. However, the specific reference here is to American politics, an association that began back in the 1860s.

Despite that, for its origin we have to look to Britain and to the stock market of the middle of the eighteenth century. The disabled bird belongs with the other members of the market’s menagerie, the bulls, bears and stags (more on the first two here). London stockbrokers and jobbers operated from coffee houses such as Jonathan’s and Garraway’s in a little street called Exchange Alley, close to the main commodity trading centre, the Royal Exchange.

The street name was often abbreviated to Change Alley or just the Alley. It still exists, now officially called Change Alley, as a network of five back streets of no particular distinction in the City of London. The coffee houses are long gone; the jobbers and brokers left even earlier, decamping to a specially constructed building in Sweeting’s Alley in 1773, which later became the Stock Exchange.

About 1760, some wit created the term for stock market traders who failed to pay up when bills became due, effectively bankrupting themselves and leading to their being barred from trading. Among the first people to use the term was the antiquarian and MP Horace Walpole, the son of Sir Robert Walpole, the man usually regarded as the first British prime minister. He was puzzled by the language of the trade:

Apropos, do you know what a Bull, and a Bear, and a Lame Duck are? Nay, nor I either: I am only certain that they are neither animals or fowl.

A letter to Sir Horace Mann by Horace Walpole, 28 Dec. 1761.

Walpole clearly kept a close ear on evolving language because the currently earliest known example appeared in the Newcastle Courant on 5 September that year, in a brief report of moneys being paid by subscription into the Bank of England, with a note that there were “No lame ducks this time”. Within a couple of months the term began to appear in London newspapers and quickly became common. This is the earliest metropolitan example that I’ve so far unearthed:

Thursday a Lame Duck disappeared from J———’s, to the no small Mortification of his Brother Bulls and Bears, whom he has touched very considerably. ... Yesterday four more Lame Ducks took their Flight.

London Evening Post, 21 Jan. 1762.

It’s easy enough to see how the lame part came about, a figurative reference to a person injured through inability to maintain his financial position. But no reference of the time that I can find makes clear why they were visualised as ducks. It might, at a stretch, be a rhyme with luck, I suppose.

Almost every one of the many later references to these failed traders refers to them as waddling away, an early example being in the Leeds Intelligencer on 29 June 1762 (emphases in the original): “Yesterday a lame duck or two made shift to waddle out of ’Change Alley”. Perhaps they were low-slung portly gentlemen, the eighteenth-century equivalent of today’s fat cats, and the way they walked suggested a duck with a bad foot? More probably, having established that failures were to be called lame ducks, the derisive image of them struggling away limping was too good not to use.

Incidentally, I can find no examples of lame duck being used literally before it took on this sense. This casts doubt on the commonly stated view that failed financiers were called lame ducks because they resembled an injured bird that was unable to keep up with the flock and so was more vulnerable to being attacked by a predator. And the failures of lame ducks in any case were usually due to their over-stretching themselves in speculative ventures, not being brought down by others.

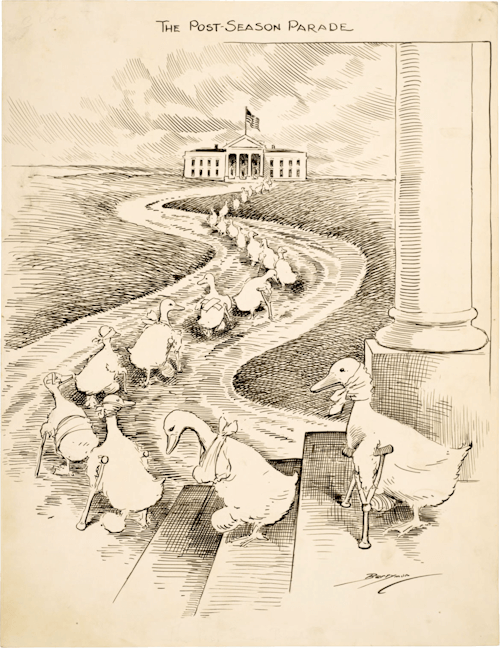

Democrat lame ducks head to the White House from Congress in May 1915, hoping to secure political appointments from President Woodrow Wilson. (Cartoon by Clifford K Berryman.)

The term was taken to North America and came to mean there a financially unstable or insolvent undertaking. Its association with Washington politics is said to have begun in 1863. It refers to an elected politician who is coming to the end of his or her period in office and so has little or no time left to do anything effective. More strictly, it means one at the very end of that period, after a successor has been elected but before his or her term actually ends. At one time, this period was several months, which tempted representatives to use their final time in office to act in a way that benefitted only themselves. Scandals led to the 20th amendment to the constitution in 1933, sometimes called the Lame Duck Amendment, which shortened the period between elections and new members taking office.