Haywire

QFrom Richard D Stacy: I recently saw the word haywire in print. From the context, I think that it means something that is not working properly. What is its etymology?

A Might your query be prompted by the recent release of the Steven Soderbergh thriller by that title?

Our modern sense of haywire is an interesting example of semantic drift. In the US of the latter part of the nineteenth century, hay wire (also commonly called baling wire, which is now what people usually call it) was literally a type of thin wire. In addition to tying together bundles of hay after cutting, it fastened bundles of grain stalks that had been cut by a horse-drawn reaper.

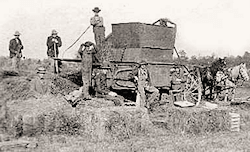

A hay baler in Ohio, early twentieth century

A hay baler in Ohio, early twentieth century

But its uses went far beyond this. It was the duct tape of its era, the stuff you reached for when you had anything to mend, one of the world’s versatile repair materials. If you needed to fix a broken barn-door hinge, the tailboard of a wagon, or a hole in a chain-link fence, you turned to hay wire. The first instance of the term I’ve been able to find records a particularly melancholy improvised use:

A young man named Samuel C. Hoyd who resided on the Mesa, South Pueblo, committed suicide on the 20th by hanging himself to a cottonwood tree with a piece of bale hay wire.

Daily Gazette (Colorado Springs) 22 Jul. 1881.

This is a famous description of the wide utility of the stuff:

No logging camp could operate without axes, and in time it came to be that no camp could operate without haywire. This wire was the stuff with which hay for the oxen and horses was bound into bales, for compact toting into the distant camps. ... Loggers used the strands to strengthen an axe helve or to wind the split handle of a peavey. Cooks strung haywire above the stove over which to dry clothes and to hang ladles; and often to bind the very stove together. In the zither era, so old-timers have vowed, a length of haywire came in handy to replace a broken string, and they say never was a more resonant G sounded, clear and deep as any harp.

Holy Old Mackinaw: A Natural History of the American Lumber-Jack, by Stewart Holbrook, 1938. A peavey is a lumberman’s hook with a spike at the end, named after its inventor, blacksmith Joseph Peavey.

There was a dark side to this. Around 1900 the term hay-wire outfit appeared, for a ramshackle, poorly equipped or roughly contrived business, one figuratively held together by hay wire. Later, a thing was described as haywire if it was broken or not working properly: it’s gone haywire, people would say.

The only thing that can be said in favor of the electric light company when the lights go out is, perhaps, its inability to make the meter go around when the juice has gone haywire.

Daily Globe (Ironwood, Michigan), 9 Sep. 1921.

A contributor to American Speech in 1925 noted that this and similar phrases, such as I feel haywire all over, had been known to him from boyhood in the language of loggers. In literalness the term may have begun on American farms but that the road to figurativeness ran through the lumber camps.

It was just a small step to applying haywire to people who were metaphorically broken — out of control, mentally confused, erratic or crazy. In this early case, the speaker is applying it to himself when speaking to a young woman:

I didn’t come out here tonight to lie to you. I’ve gone hay-wire about you, and I’ve come to tell you so.

Burlington Hawk Eye (Iowa), 14 Sep. 1927.

Readers with memories of hay wire suggest that the character of the wire itself has been a significant factor in the development of the sense of something or somebody being out of control. Hay wire pulled off its coil to use it would retain a bend and, if unrestrained, would curl up into an impenetrable jumble. Similarly, when the wire around a bale — under considerable tension — was cut to use the hay, the pieces would snap apart in an uncontrolled and even dangerous way. Tossed aside, they would tangle with others to make a snarled mass.

My experience of farming is limited to childhood visits to my elder brother, then a cowman on an Oxfordshire farm. His equivalent was baler twine or baling twine, an equally universal panacea for all malfunctions. Several humorous websites list “101 uses for baling twine” and the stuff even has its own Facebook page. A modern example:

Where my uncle’s machines were held together with baler twine, cardboard and rubber-solution glue, the machines in here had all been crafted from high-quality alloys.

Lost in a Good Book, by Jasper Fforde, 2002.