Dude

Q From Robert W M Greaves: I was taken aback to read the following in Jerome K Jerome’s book Three Men in a Boat, which was published in 1889: ‘Maidenhead itself is too snobby to be pleasant. It is the haunt of the river swell and his overdressed female companion. It is the town of showy hotels, patronised chiefly by dudes and ballet girls.’ Just how long have dudes been with us?

A Many people have come across references to dudes in connection with dude ranches, where urbanites could experience a sanitised version of Western life, and it is often assumed that this is the source of the term. However, dude ranch is relatively recent, with the first known examples being from 1921. The Oxford English Dictionary’s first example of dude is from 1883. It’s definitely an Americanism. So what was it doing, unremarked as a foreignism, in a British book as early as 1889?

The cause was an extraordinary craze or fashion identified by that name which erupted in New York in early 1883. On 25 February, the Brooklyn Eagle noted an addition to the language:

It is d-u-d-e or d-o-o-d, the spelling not having been distinctly settled yet. Nobody knows where the word came from, but it has sprung into popularity within the past two weeks, and everybody is using it... The word “dude” is a valuable addition to the slang of the day.

A description of the dude, model for all that followed, appeared in the New York Evening Post early the following month:

A dude is a young man, not over twenty-five, who may be seen on Fifth Avenue between the hours of three and six, and may be recognized by the following distinguished marks and signs. He is dressed in clothes which are not calculated to attract much attention, because they are fashionable without being ostentatious. It is, in fact, only to the close observer that the completeness and care of the costume of the dude reveals itself. His trousers are very tight; his shirt-collar, which must be clerical in cut, encircles his neck so as to suggest that a sudden motion of the head in any direction will cause pain; he wears a tall black hat, pointed shoes, and a cane (not a “stick”), which should, we believe, properly have a silver handle, is carried by him under his right arm, (projecting forward at an acute angle, somewhat in the manner that a sword is carried by a general at a review, but with a civilian mildness that never suggests a military origin for the custom). When the dude takes off his hat, or when he is seen in the evening at the theatre, it appears that he parts his hair in the middle and “bangs” it. There is believed to be a difference of opinion among dudes as to whether they ought to wear white gaiters.

The article noted that dudes, unlike the mashers of the time and the dandies, fops and swells of earlier generations, set out to give an impression of protest against fashionable folly and of being instead serious-minded young men with missions in life: “A high-spirited, hilarious dude would be a contradiction in terms.” But dudes were also widely reported as being vapid, with no ideas or conversation.

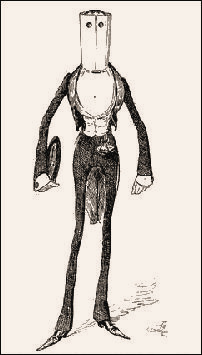

Above:A cartoon from the New York publication The Hatchet of 15 Dec 1883; below: Another cartoon, from 1888, mocking the dude fashion for high collars.

The Brooklyn Eagle fleshed out this portrait by noting that a dude was as a rule a rich man’s son, was effeminate, aped the English, had as “his badge of office the paper cigarette and a bell-crown English opera hat”, was noted for his love of actresses (to the extent of carrying on scandalous “affairs”) but with no knowledge of the theatre.

In June, the Daily Northwestern reported that dudes had taken to wearing corsets, “in order to more fully develop and expose the beauties of the human form divine”. The Richwood Gazette of Ohio argued in July that the dude was useful “as an example of how big a fool can be made in the semblance of a man”; the Prince Albert Times of Saskatchewan noted the same month that “The dude is one of those creatures which are perfectly harmless and are a necessary evil to civilization.” The Manitoba Daily Free Press reported the story, “bearing evident marks of reportorial invention”, that a dude was seen being chased up Fifth Avenue, by a cat.

You will note that dude was a term of ridicule, not approval. The geographical spread of the references shows that the whole of North America was variously intrigued and disgusted by the spread of the dude phenomenon in the cities of the East Coast. The Atlanta Constitution wrote in June, “So great a success the dude has had here in the United States, most every newspaper in the country has written editorials on him and brought him before the public in such manner as to create comment, if not surprise.” News of him crossed the Atlantic very quickly. In fact, the OED’s first example of the word is from The Graphic, a popular illustrated paper of London. Its report in March 1883 reads as if it were cribbed from the New York Evening Post: “The one object for which the dude exists is to tone down the eccentricities of fashion ... The silent, subfusc, subdued ‘dude’ hands down the traditions of good form.”

Dude became widely known in the UK and it isn’t surprising that Jerome K Jerome came across the term, as he was at the time an actor in London. Indeed, some American newspapers stated at the time that the term had been brought to New York from the London music halls and that this was the reason for the pronounced Anglophile streak in the fashion. But, so far as I know, nobody has found British examples that predate the US ones.

That leaves us without any direct leads to the source of dude. We may leave aside the theory of Daniel Cassidy in his book How the Irish Invented Slang, that it is from the Irish word dúid for a foolish-looking fellow or dolt, since he provides no evidence. But it has been plausibly linked by etymologists to the much older duds for clothes, which could especially refer to ragged or tattered ones or even to rags (hence, at the very end of the nineteenth century, dud meaning something useless); dudman was an old term for a scarecrow. We may guess that dude was a sarcastic way to describe the understated but foppish dress of these fashionable young men.