The balloon’s gone up

Q From Roger Kapp: I’ve read the phrase the balloon’s gone up (or variations) in several British-authored books, especially in those having to do with war. What is the derivation of this?

A The usual sense of the idiom is that some action, excitement, or trouble has started, often but by no means always military. It’s closely associated in memory with the Second World War, as here:

“The balloon’s gone up,” he said. “You mean Rommel has attacked?” “Yes, there’s a tank battle going on now this side of the Gazala Line.”

The Conquest of North Africa, by Alexander G Clifford, 1943. Mr Clifford was a British war correspondent for the Daily Mail.

Today, it’s possible only to use it humorously:

Take a seat, Double-Oh Nine. Look, I won’t beat about the bush. Balloon’s gone up in Patagonia. Our old friend Blofeld is threatening to launch a nuclear warhead at the polar icecap.

The Independent, 15 May 2007. In John Walsh’s irreverent riff on an advertisement by MI6 for new staff.

In this next instance, the meaning is that a deception has been exposed and that difficulties have ensued:

“I still want to know who this other young woman is.” Patrick turned with relief as Julia, cool and aloof, came into the room. “The balloon’s gone up,” he said. Julia raised her eyebrows. Then, still cool, she came forward and sat down. “O.K.,” she said. “That’s that. I suppose you’re very angry?”

A Murder is Announced, by Agatha Christie, 1950.

It would be reasonable to assume that it dates from the period of the Second World War. It brings to mind — at least it does for those of us replete in years — the raising of defensive barrage balloons over cities at the start of an air-raid to force enemy bombers to fly high. But the idiom turns out to predate not only that conflict but even the First World War. This, currently the first known example, comes from a very recently revised entry in the Oxford English Dictionary:

Being also a close-fisted chap, he hates to have the audience get more than it pays for. In brief, Alfonso, cut out the musical extras or your balloon goes up.

Putnam’s Monthly, 1909.

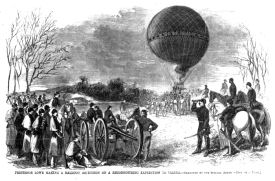

A US Civil War observation balloon.

It’s intriguing that Putnam’s Monthly was an American publication, not a British one. It can’t be an allusion to a barrage balloon, since they hadn’t been invented yet. It might be from a military observation balloon, as these were frequently hoisted for artillery spotting purposes during a battle — this is sometimes given as the origin. Alan Turner tells me that observation balloons were used in the 1860s during the American Civil War, information from spotters being passed to the ground by the newfangled electric telegraph. It may be that the expression grew out of soldiers’ experience with them in that war and the writer of this next quotation — written less than a decade after the war’s end — could have had that type of balloon in mind:

The first huge pioneer balloon has gone up in the shape of the following strange, long, and may we not say windy document in the New York Evening Post.

Dwight’s Journal of Music (Boston), 1873.

However, in the nineteenth century there also references in British and American periodicals to literal balloons going up. These were manned hot-air balloons and the launch of one was a rare event that was excitedly anticipated and well attended.

As matters stand, it’s not possible to do better than this. It’s even possible that both observation balloons and civil ballooning contributed to the idea. However, the earliest quotations imply that the idea was originally American.

A The usual sense of the idiom is that some action, excitement, or trouble has started, often but by no means always military. It’s closely associated in memory with the Second World War, as here:

“The balloon’s gone up,” he said. “You mean Rommel has attacked?” “Yes, there’s a tank battle going on now this side of the Gazala Line.”

The Conquest of North Africa, by Alexander G Clifford, 1943. Mr Clifford was a British war correspondent for the Daily Mail.

Today, it’s possible only to use it humorously:

Take a seat, Double-Oh Nine. Look, I won’t beat about the bush. Balloon’s gone up in Patagonia. Our old friend Blofeld is threatening to launch a nuclear warhead at the polar icecap.

The Independent, 15 May 2007. In John Walsh’s irreverent riff on an advertisement by MI6 for new staff.

In this next instance, the meaning is that a deception has been exposed and that difficulties have ensued:

“I still want to know who this other young woman is.” Patrick turned with relief as Julia, cool and aloof, came into the room. “The balloon’s gone up,” he said. Julia raised her eyebrows. Then, still cool, she came forward and sat down. “O.K.,” she said. “That’s that. I suppose you’re very angry?”

A Murder is Announced, by Agatha Christie, 1950.

It would be reasonable to assume that it dates from the period of the Second World War. It brings to mind — at least it does for those of us replete in years — the raising of defensive barrage balloons over cities at the start of an air-raid to force enemy bombers to fly high. But the idiom turns out to predate not only that conflict but even the First World War. This, currently the first known example, comes from a very recently revised entry in the Oxford English Dictionary:

Being also a close-fisted chap, he hates to have the audience get more than it pays for. In brief, Alfonso, cut out the musical extras or your balloon goes up.

Putnam’s Monthly, 1909.

A US Civil War observation balloon.

It’s intriguing that Putnam’s Monthly was an American publication, not a British one. It can’t be an allusion to a barrage balloon, since they hadn’t been invented yet. It might be from a military observation balloon, as these were frequently hoisted for artillery spotting purposes during a battle — this is sometimes given as the origin. Alan Turner tells me that observation balloons were used in the 1860s during the American Civil War, information from spotters being passed to the ground by the newfangled electric telegraph. It may be that the expression grew out of soldiers’ experience with them in that war and the writer of this next quotation — written less than a decade after the war’s end — could have had that type of balloon in mind:

The first huge pioneer balloon has gone up in the shape of the following strange, long, and may we not say windy document in the New York Evening Post.

Dwight’s Journal of Music (Boston), 1873.

However, in the nineteenth century there also references in British and American periodicals to literal balloons going up. These were manned hot-air balloons and the launch of one was a rare event that was excitedly anticipated and well attended.

As matters stand, it’s not possible to do better than this. It’s even possible that both observation balloons and civil ballooning contributed to the idea. However, the earliest quotations imply that the idea was originally American.