Newsletter 798

18 Aug 2012

Contents

1. Feedback, Notes and Comments

Holiday break World Wide Words will not appear next week — my wife and I are taking a short trip away. The issue of 1 September is the next scheduled one.

Strickle Many readers noted that this tool resembled in function and name the strigil, one with a curved blade that Romans used in the baths to scrape dirt and sweat off their bodies. The similarity is misleading, as no link exists: strigil is from the Latin verb stringere, to touch lightly. The latter is the source of one old sense of the English word stricture, likewise to touch lightly. (Its other senses are from another Latin verb of the same spelling, meaning to bind tightly.)

Another word with similar associations is screed, a strip of wood or other material to set a level for laying concrete or applying plaster (we meet it more often in the sense of the result). This again has a different history: it once meant an edge or bordering strip, from which the current sense derives. It was earlier a strip or fragment cut or torn from a larger piece — the Old English original is also the source of shred.

Out of school A quotation of 1833 in the piece on talking out of school last week referred dismissively to “riding schools and schools for scandal”. The second allusion was obvious but the first puzzled me. I have led too sheltered a lexicographical life. Bruce Napier suggested riding school was a low slang term of the time for a brothel. This is supported by the related term riding academy being on record in this sense. And you may not know that a confusion between the two meanings of riding school was the basis of a South African film of 1981, Birds of Paradise.

2. Weird Words: Wardour-Street English

I caught myself using the obsolete word withal in an e-mail to a subscriber last week and out of interest looked it up. I was deeply chastened to find it dismissed as a Wardour-Street word in every edition of Fowler’s Modern English Usage back to the first of 1926. It is not a compliment.

In my younger days, London’s Wardour Street was a metaphor for the British film industry, which was based in and around it. No longer. As the Sunday Times wrote in May 2012, “The movie companies, which had great window displays all along Wardour Street, have gone.” To men of an earlier generation, such as H W Fowler, the associations of the street were instead with dealers in antique furniture and imitations thereof.

Thereof: I am doubly reproved. Henry Fowler included it alongside withal in his collection of Wardour-Street words, alongside wot, thither, varlet, howbeit, belike, albeit, betimes and numerous others. He wrote of them in sarcasm of deepest hue:

As Wardour Street itself offers to those who live in modern houses the opportunity of picking up an antique or two that will be conspicuous for good or ill among their surroundings, so this article offers to those who write modern English a selection of oddments calculated to establish (in the eyes of some readers) their claim to be persons of taste & writers of beautiful English.

A Dictionary of Modern English Usage, by H W Fowler, 1926.

Wardour-Street words are borrowed especially by the authors of bad historical fiction who adopt the “Prithee, sirrah!” and “Have at ye, thou scurvy varlet!” schools of exposition. They follow writers of an earlier age, above whom towers Sir Walter Scott, who single-handedly invented the historical genre and resurrected many antique words with which to decorate it.

Wardour-Street English sounds like a phrase that Fowler might have invented. But it’s older. Its creator, writing in Longman’s Magazine in October 1888, was a historian named Archibald Ballantyne, who had the year previously published a biography of the eighteenth-century statesman Lord Carteret.

He was ridiculing attempts by a group that included the Dorset poet William Barnes to expunge foreign elements from the language. Their ideal was to return to the “purity” of pre-Conquest “Anglo-Saxon” English through inventing replacement terms on Old English roots, such as fireghost for electricity, gleecraft for music or high-deedy for magnificent. Ballantyne also mocked William Morris, in particular his translation of the Odyssey, full of terms such as thrall-folk, dight and yeasay. He wrote of it, “This is not literary English of any date; this is Wardour-Street Early English — a perfectly modern article with a sham appearance of the real antique about it.”

In the same way that an unscrupulous dealer might distress a modern piece of furniture to create a spurious impression of age, argued Ballantyne, so writers who clothe their prose in the cast-offs of ye olde Englyshe are producing poor fakes. Elderly lexicographers who spend so much of their time reading old texts that they have picked up obsolete turns of phrase may surely be excused this condemnation.

The term is less used than it once was but may still be found:

Massie then settles down into a species of Wardour Street English not seen since the days of W.H. Ainsworth and G. P. R. James, in which a horse is always a trusty steed or even a “palfrey”, the wretched Alory, absconding bearer of the Oriflamme, is branded ‘a coward and a poltroon’ and Elgebast warns the esquires Ivor and Yves that “if you play me false I shall split the pair of you from gizzard to guts”.

In a review of Charlemagne and Roland by Allan Massie in the Spectator, 11 Aug. 2007.

3. Wordface

Where the toad sucks ... This column doesn’t often feature toponymic matters, but I can’t resist noting the results of a survey published last week which named the 10 most unfortunate place names in the United States, as voted upon by visitors to a genealogical site. Top of the list came the estimable Arkansas community of Toad Suck. The others, in decreasing ranking, were: Climax, Boring, Hooker, Assawoman, Belchertown, Roachtown, Loveladies, Squabbletown and Monkey’s Eyebrow. There are many others worldwide. Don’t tell me about them, please ...

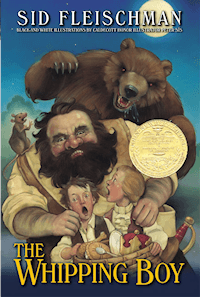

4. Questions and Answers: Whipping-boy

Q From Jonas Withers: I’ve just read that somebody had become a whipping-boy. Where does this come from? Was he ever a real boy?

A He was, and it’s one of the stranger stories in word history.

First off, a whipping-boy is a scapegoat, a person who suffers punishment because of the faults of somebody else. Here’s a recent example:

Sorkin is well aware that he is a whipping-boy for a swathe of America — he’s the preppy liberal with a big ego they love to hate.

Sunday Times, 8 Jul. 2012. The context is Aaron Sorkin’s TV show The Newsroom.

These days, whipping-boy is as figurative a term as scapegoat. We don’t any longer load all the sins of a community on to a goat and send it into the wilderness and similarly we don’t chastise a child for the naughtiness of another. But we once did.

The term seems never to have been attached literally to anybody much below the companion of a prince. The earliest on record — though no doubt there were previous examples — was an Irish lad named Barnaby Fitzpatrick (or Fitzpatric or Fitz-Patric). His father sent him — at the age of six or thereabouts — to the English court in 1543 to be a companion to Prince Edward, later Edward VI. He was said to have been regularly punished for Edward’s misdeeds. A play early the following century about Henry VIII and the young Prince Edward features a fictional version of him:

Prince: Why, how now, Browne; what’s the matter?

When You see Me You know Me, by Samuel Rowley, 1604.

A modern take on an old story

A modern take on an old story

It has often been suggested that the system grew up because the prince’s tutors daren’t lay a hand on the prince and so punished his companion. It’s more probable that it was a better way of keeping the prince well-mannered than direct punishment, since he knew that if he transgressed his companion would suffer instead.

It must have been difficult for young Barnaby, but he briefly did well out of it. He became an intimate of the future king and was sent to France to complete his education. However, Edward VI died in 1553, aged only 15, and hope of preference vanished. Half a century later, in 1603, another boy, the even younger William Murray, was placed by his father in a similar situation with Prince Charles, later Charles I. Murray did better than Fitzpatrick: he later became the first Earl of Dysart and a confidant of the king, working even after Charles’s execution to put Charles II on the throne.

The term whipping-boy wasn’t around at the time of either of these boys — it was sometimes known as “punishment by proxy”. The first known user of whipping-boy was a clergyman named John Trapp in a Biblical commentary in 1647.

5. Sic!

• A BBC piece on 6 August, headlined “High flying technology to map Peru ruins”, delighted Stephen Conroy with this sentence: “Small enough to fit in a backpack, Professor Adams hopes the device would be able to be used by any researcher.”

• A report on MoneyWeb in South Africa, seen by Colin Day in Cape Town, quoted a comment by a firm of attorneys: “The warrants have been issued unlawfully and unconstitutionally and in fragrant violation of our client’s rights.”

• Freudian slip? Chas Blacker read a comment from one of Britain’s veteran medal winners in the Independent on 7 August: “‘My hip’s great,’ said Skeleton, ‘It’s my back that’s the problem now.’” The speaker was actually show-jumper Nick Skelton.

• Thanks go to Richard Kuebbing for sending us this report on Yahoo! News, dated 14 August, which began “A nearly 400-foot deep sinkhole in Louisiana has swallowed all of the trees in its area and enacted a mandatory evacuation order for about 150 residences for fear of potential radiation and explosions.”

• Definitely a headline to make you read it twice — Richard Moloney found it in the Irish Times on 14 August: “Cruise ship makes maiden stop in Dublin”. Accidental wording, or sub-editor’s joke?