Newsletter 772

04 Feb 2012

Contents

1. Feedback, notes and comments

Macmillan competition We came third. The English Club was second. The winner was Wordsmith, the home of Anu Garg’s A Word A Day, which came romping up from behind at the last minute. But then his daily e-mail newsletter has rather more than a million subscribers, which makes World Wide Words’s 50,000 readers look paltry. I’m delighted he has won: he deserves to. Many thanks go to everybody who supported World Wide Words. And a special welcome to all who have subscribed through learning about us via the competition.

Haywire Several readers argued that there was a specific reason why going haywire took on its sense of being out of control. Ken Shaw commented: “I was taught that when something went haywire, it was not only not working properly but was also dangerous. Hay bales are bound very tight. If the haywire snapped or was cut to open the bale, the ends whipped around and could inflict serious injury.”

Others suggested that the term referred to the way in which baling wire left to its own devices would at once form a tangled mess. As David Means remembers, “When [farmers] would ‘bust’ a bale to use as feed for the livestock, typically the used loop of wire was tossed into an old washtub or a certain corner of the barn, where it was available for re-use somewhere else on the farm. Once there were a number of these wire pieces in the pile, they tended to get tangled when someone attempted to pull one out. This snarled mass was always difficult to work with, and that is the sense of the term ‘haywire’ that was passed to me: something that was almost hopelessly beyond repair or so contorted that it would take a long time to rectify.”

John C Britton recalled another expression: “I heard as a child that something was held together with bubble gum and baling wire, being a by-gosh and by-golly emergency repair, that became the permanent fix, by gum.”

Can anybody help? A query came from Anne Osborne in the UK: “An expression long in use in my family is going on teacakes and haybands. It is usually used about a clock behaving erratically, either gaining or losing. Does anyone else use it?”

2. Weird Words: Standing pie

This old regional English term is now known mainly to cooks who have historical interests. A century ago, it was better known:

Hotels and inns provide a huge game pie for their customers, ‘standing pies’ they are called, being nearly a foot high, and filled with the choicest morsels of hare, rabbit, pheasant, &c.,

Folk-Lore, by Edward Nicholson, 1890.

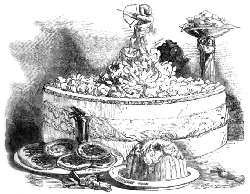

An ornate standing pie, from The Illustrated London Cookery Book by Frederick Bishop, 1852

The origin lies in a technique, known from medieval times, in which a pastry case was created separately from its contents. Coarse flour and water were moulded like clay into the shape required and then baked hard. It was inedible in itself but served in the absence of suitable ceramics to hold whatever was being baked, which might be almost anything — meat or fish as well as game. They were called standing pies because the pastry cases stood by themselves. Such constructions were often ornate showpieces at banquets. The cases were usually thrown away after one use, though one source has stated that they were “given to the hounds or to the poor”, which seems hard on the teeth and stomachs of either.

The standing pies of rural communities were more modest than those Mr Nicholson described. They usually contained a mixture of beef and suet seasoned with apples and dried fruit. Such pies were the high-energy food of hard-working farmers and agricultural labourers, as described here by one farmer in the Cumbrian dales a century ago, using his local dialect form of the term:

The other sort is a “stannin’ pie,” made like a pork pie and often as hard to cut into as a brick. This will keep any length of time, and the housewife finds it handy to offer cold to any chance visitor, if only she can hide it from the lads; but they have as keen a nose for sweet pie as they have for the rum butter we make at a christening and hide from them.

Manchester Guardian, 26 Dec. 1903.

3. Wordface

Words of 2011 The results were announced on Wednesday of the Macquarie Dictionary’s Australian Word of the Year awards for 2011. It’s the most complex of all the public contests, with votes requested for lists of words in 16 different categories. The Word of the Year is selected from among the category winners by the Word of the Year Committee, which is chaired by the Vice-Chancellor of the University of Sydney, Dr Michael Spence.

The overall winner (and I chose that word with care) was burqini (often written as burkini), the all-enveloping modest swimsuit designed for Muslim women, whose name is a blend of burqa and bikini. It has been around since at least 2006 in the UK, when it was mentioned in the Independent on Sunday by columnist Deborah Ross; its relevance to Australia in 2011 is due to the British cookery broadcaster and writer Nigella Lawson, who wore one on Bondi Beach in April. One of the committee, David Astle, commented, “As a wordsmith I am delighted by a word that has Q without U and ends with an I.”

Another winner, The People’s Choice Award, derives from the voting on the website. This year, the word is fracking, in the news in the US and UK as well as Australia. It’s a shortening of fracturing and is the process by which gas and oil are extracted from shales underground by applying chemically treated water under pressure. It’s mostly linked in the public mind with stories of groundwater contamination and earth shocks. A report by Jonathan Fahey of the Associated Press on 26 January said that the industry prefers frac and fraccing and argues that the k was added by opponents to make it more like the F-word and to suggest the violent connotations of words such as smack and whack.

Three of the winners of individual categories drew the attention of the committee. A patchwork economy refers to a country in which some parts are doing well while others are less prosperous. As a phrase, it has been common in several countries for many years, but became part of the Australian political vocabulary in April 2011 when it was used by the prime minister, Julia Gillard. The Macquarie Dictionary’s publisher, Sue Butler, commented in the Sydney Morning Herald on 31 December that the phrase is “more homely and domestic” than others such as “two-speed economy”.

Dairyness, from the Agriculture category, was a strange choice. It refers, the Macquarie Dictionary says, to the productivity of a cow in terms of the quality and quantity of its milk, assessed by udder shape and size, pedigree, genomic screening and other factors, which are used as judging criteria in competitions. As a specialist term it has been recorded in North America since the 1950s but a search of the newspaper archives of Australia that I have access to found no trace of it.

The last was announceable, not an adjective but a noun from Australian politics. Again, it’s not that common in newspapers, though when it does turn up it’s clear that it’s firmly established. This is how the Courier & Mail of Brisbane explained it in July 2010: “One state politician has been known to stride into the office on a bad news day demanding: ‘Christ, what a stuff-up. Get me some announceables.’ Put simply, for politicians, an announceable is something you go public on to make you look good. The announceable is something you trot out when you need a distraction. The announceable is something for when the ‘merde’ hits the fan.”

4. Articles: The Words of Dickens

Next Tuesday, 7 February, is the 200th anniversary of the birth of Charles Dickens. It has been impossible to avoid knowing about this impending event for several months because of way that the British media has anticipated it, with its usual concern to get ahead of its competitors. Boredom has set in for many British readers and viewers, few of whom these days read him.

I was going to pass over it in silence, not wanting particularly to add to the hoopla. But then, in an idle moment of curiosity, I fired up the Oxford English Dictionary to learn more about the linguistic legacy the man has left us. He wrote such delightful and insightful descriptions of London and its people that I wondered if his verbal inventiveness matched his artistic abilities.

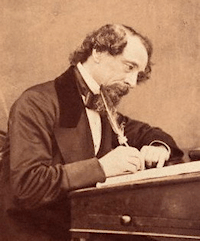

Charles Dickens

Charles Dickens

Dickens is highly rated by the OED. He is the 13th most frequently quoted source, well ahead of his contemporaries, though this may in part reflect his extraordinary output rather than his creativity. Among the 9,218 quotations from his works in the OED, 265 words and compounds are cited as having been first used by him in print and another 1,586 as having been used in a new sense.

Life’s too short to look at them all; let’s concentrate on the 265 new words and phrases. He’s credited with inventing such standard English terms as boredom, flummox, rampage, butter-fingers, tousled, sawbones, confusingly, casualty ward, allotment garden, kibosh, footlights, dustbin, fingerless, fairy story, messiness, natural-looking, squashed, spectacularly and tintack.

Anybody who cites these based on the OED’s evidence risks being regarded as out of touch. Most of the entries haven’t been revised since they were compiled a century ago. Our etymological knowledge has improved greatly since then and has had a huge boost from the introduction of searchable digitised archives. I trawled the British Library’s archive of nineteenth-century newspapers to check how original these words really were. A lot weren’t.

Boredom, for example, which Dickens included in Bleak House in 1853, is known from the Theatrical Examiner of April 1841; he used casualty ward in Sketches by Boz in 1836 but it’s known from Jackson’s Oxford Journal dated January 1825; footlights is in the same work but is earlier in the Morning Chronicle of December 1822; natural-looking is likewise from Sketches by Boz but a Mr T Hood advertised natural-looking wigs in the Morning Post a quarter of a century earlier, in November 1810; confusingly, from a letter of May 1863, is in the Morning Post of February 1852; sharp practice comes from The Pickwick Papers of 1837 but is trumped by The Bury and Norwich Post of February 1810; fairy story, which Dickens included in David Copperfield as an alternative to the older fairy-tale, may be found in the London Standard in December 1827; snobbish, in The Old Curiosity Shop of 1841, appears likewise in the London Standard, in May 1836; kibosh, also from The Pickwick Papers, has been backdated several years by recent careful research.

Other terms are certainly his to claim, including butter-fingers, unpromisingly, sawbones, messiness, spiflication, whizz-bang and seediness. Flummox appears in The Pickwick Papers of 1837 but was also included by James Halliwell-Phillipps in his Dictionary of Archaic and Provincial Words in 1846 — it seems that Dickens breathed new life into an old dialect word. Tousled, as touzled, is in Dombey & Son of 1848, but appeared four years before in the Manchester Times and Gazette of December 1844; however, this is in a story with the title Trotty Veck and the Nor’-Wester, by one Charles Dickens, so he has neatly antedated himself.

None of this detracts from Dickens’s skill in using language. He is the first recorder of many items of slang (one contemporary critic called him the professor of slang), which he didn’t invent but which his sharp ear for colloquial speech lovingly noted. In other cases he popularised colloquial terms that might without him have died out, such as kibosh and devil-may-care. He had a trick of making compound adjectives from existing words that concisely expressed a thought: angry-eyed, hunger-worn, proud-stomached, fancy-dressed, coffee-imbibing and ginger-beery, as well as new compound nouns such as copying-clerk and crossing-sweeper.

As these examples show, we must always be sceptical of claims about who invented a word. Deeper digging often demonstrates that others had got to them first. But nobody is going to be less attracted by Dickens through knowing that.

5. Sic!

• The San Francisco Chronicle’s website had a headline on 31 January (sent in by Jim Tang from Hawaii): “Ranger zaps off-leash dog walker with shock weapon”. I’ve long suspected that it’s the owner who’s on the leash, not the dog.

• Darren Zanon tells us the Mount Sinai Medical Center in Manhattan is advertising for a director of software development. Among the post’s duties: “Works with end users to establish efficient processes and excrement customer care.”

• Will Gout e-mailed about a short-lived sentence on the ABC News website on 30 January: “The ACT bomb squad has closed a Canberra street after auspicious packages were found at the Israeli and French embassies.”

• An Associated Press story dated 31 January was spotted by Richard Collins on the website of the Wisconsin State Journal: “Woman killed in car accident facing prison time”. That was, of course, before she was killed.