Newsletter 923

07 May 2016

Contents

1. Feedback, Notes and Comments

Fewmet. Many readers pointed out that I might more appropriately have quoted from T H White’s The Once and Future King of 1939; this would seem to be the source from which everybody has copied:

“I know what fewmets are,” said the boy with interest. “They are the droppings of the beast pursued. The harbourer keeps them in his horn, to show to his master, and can tell by them whether it is a warrantable beast or otherwise, and what state it is in.”

“Intelligent child,” remarked the King. “Very. Now I carry fewmets about with me practically all the time.”

“Insanitary habit,” he added, beginning to look dejected, “and quite pointless. Only one Questing Beast, you know, so there can’t be any question whether she is warrantable or not.”

Lie doggo. David Means emailed from Kansas City: “Although I am familiar with lying doggo as a term for hiding temporarily, the term I’ve heard used most often in this region is lie in the weeds, which conveys the same sense. The implication is that weeds are unkempt and tend to grow tall, so it’s easy for someone to lie down in the midst and remain relatively hidden. It’s used most often about someone who has made some gaffe, or has done something that is socially outside the pale, and needs to retire from public life for a time until it blows over.”

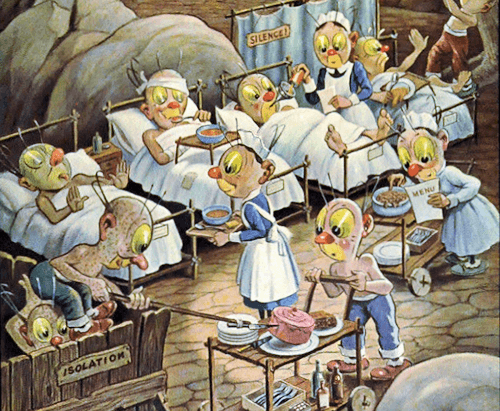

Dingbats in the 1964 Frosst calendar

Dingbat. “Allow me to add further detail to your interesting discussion,” emailed P W Bridgman. “I would venture that many Canadians of my vintage (born 1952) will remember the Charles E Frosst calendars that hung in many doctors’ offices in the 1950s and 1960s. The Frosst company was a manufacturer of pharmaceuticals and, undoubtedly, provided its calendars to physicians as part of its marketing program. The calendars are memorable for their whimsical, cartoon-like images of many stylised creatures, called dingbats, all busy at work rendering some kind of medical care or other. The images were clever, highly detailed and perfectly fascinating to children otherwise burdened with feelings of trepidation about being subjected to medical assessment. The calendars provided, I suppose, a welcome and comforting distraction from whatever indignities might be in store when, eventually, the shirt came off or (heaven forbid) the pants had to come down.”

Over to you. I haven’t been able to help Rachel Clark with a query and wonder if anybody can help. She wrote: “I recently came across a wonderful word in my grandmother’s letters and things from the 1930s or so. It is umphidilious (though I’m not positive on the spelling) and apparently means wonderful or awesome or amazing. She lived in Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe, and her heritage is mainly Dutch I believe. My dad remembers her and others using this word (and its short form umfy) quite frequently. I did a web search for this word but could find nothing.”

Holiday break. My wife and I are about to depart on holiday. The downside is that I shall have no time nor facilities to produce the June issue of the newsletter. With luck an issue will appear on 2 July.

2. Lame duck

Q From James Macdonald: During Barack Obama’s recent visit to London, some British newspapers referred to him as a lame duck president. That expression is familiar to me, of course, but I did wonder why somebody who was ineffectual or unsuccessful should be described in that strange way. Lame I can understand, but why duck?

A Lame ducks, of course, can be incompetent or ineffectual firms or governments as well as individuals — British political life has seen many examples of both described as lame ducks down the decades. However, the specific reference here is to American politics, an association that began back in the 1860s.

Despite that, for its origin we have to look to Britain and to the stock market of the middle of the eighteenth century. The disabled bird belongs with the other members of the market’s menagerie, the bulls, bears and stags (more on the first two here). London stockbrokers and jobbers operated from coffee houses such as Jonathan’s and Garraway’s in a little street called Exchange Alley, close to the main commodity trading centre, the Royal Exchange.

The street name was often abbreviated to Change Alley or just the Alley. It still exists, now officially called Change Alley, as a network of five back streets of no particular distinction in the City of London. The coffee houses are long gone; the jobbers and brokers left even earlier, decamping to a specially constructed building in Sweeting’s Alley in 1773, which later became the Stock Exchange.

About 1760, some wit created the term for stock market traders who failed to pay up when bills became due, effectively bankrupting themselves and leading to their being barred from trading. Among the first people to use the term was the antiquarian and MP Horace Walpole, the son of Sir Robert Walpole, the man usually regarded as the first British prime minister. He was puzzled by the language of the trade:

Apropos, do you know what a Bull, and a Bear, and a Lame Duck are? Nay, nor I either: I am only certain that they are neither animals or fowl.

A letter to Sir Horace Mann by Horace Walpole, 28 Dec. 1761.

Walpole clearly kept a close ear on evolving language because the currently earliest known example appeared in the Newcastle Courant on 5 September that year, in a brief report of moneys being paid by subscription into the Bank of England, with a note that there were “No lame ducks this time”. Within a couple of months the term began to appear in London newspapers and quickly became common. This is the earliest metropolitan example that I’ve so far unearthed:

Thursday a Lame Duck disappeared from J———’s, to the no small Mortification of his Brother Bulls and Bears, whom he has touched very considerably. ... Yesterday four more Lame Ducks took their Flight.

London Evening Post, 21 Jan. 1762.

It’s easy enough to see how the lame part came about, a figurative reference to a person injured through inability to maintain his financial position. But no reference of the time that I can find makes clear why they were visualised as ducks. It might, at a stretch, be a rhyme with luck, I suppose.

Almost every one of the many later references to these failed traders refers to them as waddling away, an early example being in the Leeds Intelligencer on 29 June 1762 (emphases in the original): “Yesterday a lame duck or two made shift to waddle out of ’Change Alley”. Perhaps they were low-slung portly gentlemen, the eighteenth-century equivalent of today’s fat cats, and the way they walked suggested a duck with a bad foot? More probably, having established that failures were to be called lame ducks, the derisive image of them struggling away limping was too good not to use.

Incidentally, I can find no examples of lame duck being used literally before it took on this sense. This casts doubt on the commonly stated view that failed financiers were called lame ducks because they resembled an injured bird that was unable to keep up with the flock and so was more vulnerable to being attacked by a predator. And the failures of lame ducks in any case were usually due to their over-stretching themselves in speculative ventures, not being brought down by others.

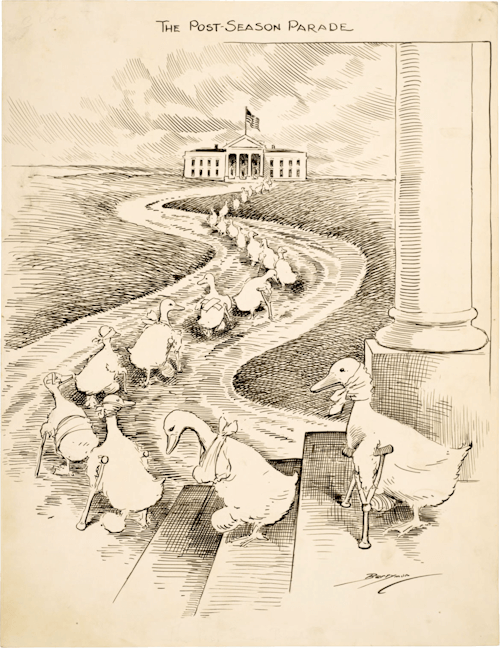

Democrat lame ducks head to the White House from Congress in May 1915, hoping to secure political appointments from President Woodrow Wilson. (Cartoon by Clifford K Berryman.)

The term was taken to North America and came to mean there a financially unstable or insolvent undertaking. Its association with Washington politics is said to have begun in 1863. It refers to an elected politician who is coming to the end of his or her period in office and so has little or no time left to do anything effective. More strictly, it means one at the very end of that period, after a successor has been elected but before his or her term actually ends. At one time, this period was several months, which tempted representatives to use their final time in office to act in a way that benefitted only themselves. Scandals led to the 20th amendment to the constitution in 1933, sometimes called the Lame Duck Amendment, which shortened the period between elections and new members taking office.

3. Logomaniac

You, dear reader, would almost certainly happily admit to being a logophile, a lover of words — why else are you here? But what if somebody called you a logomaniac? I suspect you might reject the assertion of uncontrolled passion that maniac implies.

Logomaniac was coined in the nineteenth century:

We have outgrown the customs of those logo-maniacs, or word-worshippers, whom old Ralph Cudworth in his True Intellectual System of the Universe, p. 67, seems to have had in view.

Shakespeare and the Emblem Writers, by Henry Green, 1870.

It had a brief spurt of usage in Australia at the end of the century, such as here:

What a farce must the criminal law in New South Wales be when any rantipole logomaniac can, by appealing to the passions of the “great unwashed,” suspend its machinery and render its punitive provisions and its administrators alike contemptible.

Evening News (Sydney, NSW), 30. Sep. 1895. More on rantipole.

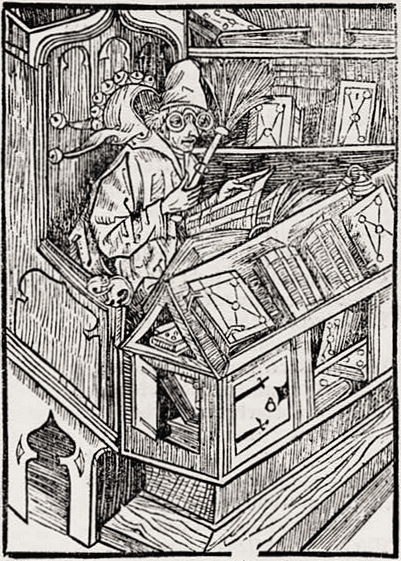

A medieval logomaniac?

Otherwise, it has only had significant exposure in the past 50 years. Perhaps because its circulation has been so limited, it comes to people fresh and unworn, like a new penny. Without much in the way of usage examples, it’s not always easy for the tyro user, or even the dictionaries, to be sure exactly what people mean by it.

Some reference works define it — certainly incorrectly — as “a person who loves words”, a simple synonym of logophile. Others generate deeper mental associations by asserting that it refers to an obsessive user of words:

[Bertrand] Russell was one of those people who wrote almost continuously; he lived his life on paper. ... The only comparable logomaniac over such a lifespan is Shaw.

The Independent, 20 Apr. 1996.

The Century Dictionary of 1899 went further still, suggesting that the obsession was unhealthy by defining logomaniac as “One who is insanely devoted to words.” A recent work implies that it may be a mental malaise, “pathologically excessive (and often incoherent) talking”, perhaps applicable to people who talk to themselves in public all the time without benefit of mobile phone. Other authors imply it may be the lesser condition of mere talkativeness:

I tried more conversational gambits than a lonely logomaniac at a singles’ bar.

Brother Odd, by Dean Koontz, 2006.

“This is just me, talking.”

“You are crazy.”

“Actually, I believe the technical term is logomaniac. It’s from the Greek: logos meaning word, mania meaning two bits short of a byte. I just love to chat is all.”

Think Like a Dinosaur, by James Patrick Kelly, 1995.

Confusingly, a more recent affliction given the same name is an obsession with brands and brand images; a logomaniac of this character might be fixated on the fashionable display of trademarked designs on articles of clothing.

While searching online for examples of the word’s usage, I came across an article — it must be hoped that it had been automatically generated as the result of my search — entitled What Is The Meaning Of Baby Name Logomaniac? We trust no loving but word-ignorant parent will foist this abomination onto their offspring.

4. But and ben

Q From Jim Black: In Scotland, one may find a style of house known as a but and ben. That’s a curious term and I’m thinking it has an interesting history. Can you help?

A I can. It’s a phrase steeped in Scottish history and culture, traditionally crofting but also rural life generally. It can evoke a poverty-stricken hardscrabble life that has at times been romanticised, as in this song by Sir Harry Lauder:

Just a wee deoch an’ doris, afore ye gang awa’;

There’s a wee wifie waitin’ in a wee but an’ ben.

Deoch an doris, a custom of a parting drink, is from Scottish Gaelic deoch an doruis, a drink at the door.

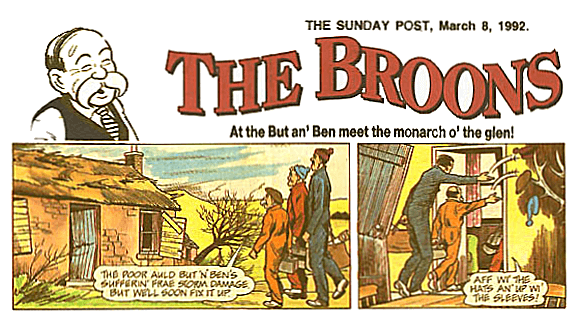

The survival of the term in Scotland has been placed squarely on the cartoon strip The Broons, which has appeared in The Sunday Post for the past 80 years. They live in the fictional Auchenshoogle, probably a district of Glasgow, but have a but an’ ben in the hills as a holiday home.

A but and ben is a two-roomed house of one story. There was usually only one door to the outside; this gave access to the kitchen, the public room in which everyday life took place and in which members of the family often slept. This led into a private inner room, where guests could be entertained and which — like many a front room or best room in poor but decent homes everywhere — was often furnished to a higher standard but less often used. If the family was large, however, the inner room could double up as a bedroom.

The outer room was the but and the inner one the ben. Putting them together the but and ben was the whole house.

The cottage had originally consisted of the usual “but-and-ben”, that is to say, in well regulated houses (which this one was not) of a kitchen — and a room that was not the kitchen. The family beds occupied one corner of the kitchen, that of Bridget and her husband in the middle (including accommodation for the latest baby), while on either side and at the foot, shakedowns were laid out “for the childer,” slightly raised from the earthen floor on rude trestles, with a board laid across to receive the bedding.

The Dew of Their Youth, by S R Crockett, 1910.

The survival of the term in Scotland has been placed squarely on the cartoon strip The Broons, which has appeared in The Sunday Post for the past 80 years. They live in the fictional Auchenshoogle, probably a district of Glasgow, but have a but an’ ben in the hills as a holiday home.

Some people have guessed that ben is Gaelic or from some Norse word. But there’s no evidence for either and the experts are now sure it’s a dialect variant of the Middle English binne, within. (If you know Dutch or German, you will be familiar with its relative binnen with the same meaning.) But is a special instance of our everyday conjunction, which stems from the Old English be-utan and which variously meant without, except or outside.

So the but was the “outside” room and the ben the room “within”.

This led to various phrases. Both words were used in the extended phrases but the hoose and ben the hoose for the two rooms. To be far ben with one meant to be a close friend, who was regularly admitted to the ben. To go but and ben was to move from the inner to the outer room and back again, hence repeatedly going backwards and forwards, to and fro. Since the but and the ben constituted the whole house, but and ben could also mean everywhere.

Blithe, blithe and merry was she,

Blithe was she but and ben:

Blithe by the banks of Ern,

And blithe in Glenturit glen.

Blithe Was She, by Robert Burns, in The Works of Robert Burns, 1800.

Families occupying two-roomed apartments in tenements, which led off a common passage as close neighbours, were said to be living but and ben.

5. Type louse

Q From Martin Schell: I enjoyed your recent piece on dingbat and noticed that one quotation mentioned type-lice. What does this term refer to?

A The species has not been well studied scientifically but has been identified on occasion as Pediculous typus or Pyroglyphidae typographicus; at one time it was called the typographical beetle. British printing shops seem thankfully free of the pest but a search among writings by American printers and newspapermen produced many descriptions of the damage that these little beasts could do. The Cedar Rapids Tribune of January 1947, for example, described them as “the traditional fly in the printer’s ointment”.

They were reported to feed on type, the resulting gnaw marks requiring the affected type to be thrown away. They liked to secrete themselves among type, sometimes, it was said, in the fl and fi ligature compartments of type cases where they would be least disturbed, They were often held responsible for errors in setting type and even of rearranging the type to make nonsense words.

This is how one Canadian publication explained them:

In the old days, when this newspaper was printed by means of what is called the hot-lead system, many so-called simple errors were caused by type lice. Type lice laid their eggs in the bottoms of galley trays. There they hatched. There they spent their lives. And there they created their havoc. If printers carelessly left the lead type in these galley trays for extended periods of time, the type lice would actually consume amazingly large quantities of lead, often making a’s look like o’s, turning 2’s into 3’s and worse.

The Brandon Sun (Manitoba), 6 Mar. 1975.

The same article reported that in recent years type lice had built up such a strong natural immunity to insecticides that serious infestations of the creatures had made hot-lead composition all but impossible. The downside of consequent advances in technology, such as computer typesetting, has been a serious loss of habitat, leading to a severe decline in the numbers of type lice; if not actually extinct they are now restricted to small print shops still using hot or cold metal type.

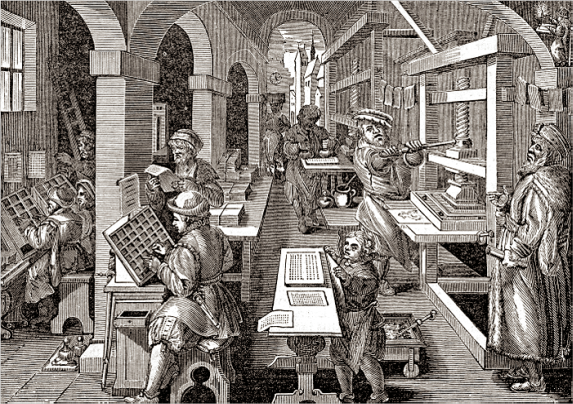

Type lice may have already in residence in early print shops such as

this Dutch one of the sixteenth century.

The first reported appearance of the type louse was in The Hancock Jeffersonian of Findlay, Ohio, in May 1869 (“the poor printer is often compelled to explain and show everything about the office, even down to the type lice”), though it’s hard to be sure this is the same species as others mentioned from time to time; as this description explained, type lice were difficult to conclusively identify:

The type louse is like the common Pediculus capilus, in that it is a wingless, hemipterous insect, but it is unlike in the fact that it is continually undergoing metamorphosis and no two persons ever saw the insect the same, nor no one person ever saw it twice in the same place or same condition.

The Evening Times (Monroe, Wisconsin), 5 Jun, 1895.

Young apprentices, traditionally called printer’s devils, were often told about the lice by seasoned journeymen on first arriving in the shop, who would promise to show the boys an example. When one was spotted, the nuisance potential of the type louse was such that attempts to point it out invariably led to unfortunate consequences:

The foreman of the office where I began promised to show me a type-louse — and he kept his promise. One day while he was making up a form on the imposing-stone — that is, placing the set type between the column rules and sopping it down with a wet sponge, as printers do in country offices, he exclaimed, “Come quick, Newt — here’s a type-louse!” I rushed to his side. “Right there it is,’’ he whispered: “bend close to that type and look sharp!" I followed instructions and while I was rubbering diligently he socked together, under my nose, two sections of water-soaked type with great violence, whereupon the water squirted up into my expectant face and eyes.

The Boston Post, 6 Apr. 1922.

As the Morgantown Dominion News wrote in March 1969, the type louse “played an important role in the training of the novice printer”, equivalent to the left-handed monkey wrench, ready-made posthole, tartan paint, spare bubbles for spirit levels and buckets of steam known in other trades.

6. Corium

Q From Chester Graham: I came across the word corium in a strange online article about nuclear reactor disasters. I looked it up in my favourite dictionaries, where it means one of the layers of skin. Has the writer made a serious mistake?

A We must forgive your favourite dictionaries for not including corium. Though it’s a real word with a distinct meaning, it’s part of the specialist jargon of nuclear safety experts and almost totally unknown to the wider world.

It seems to have been invented by the team investigating the Three Mile Island nuclear accident in 1979. They used it to describe the mass of lava-like molten fuel, fission products, control rods, structural materials and concrete that flowed into the base of the reactor after it had overheated.

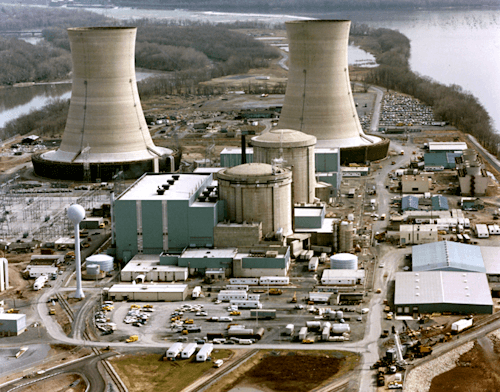

The Three Mile Island nuclear generating station before the 1979 accident.

I’ve not been able to track down the origin in more detail but it was almost certainly created as a compound of core with the suffix -ium that usually marks a chemical element. I’d guess it was a black joke, created to relieve the awfulness of the situation confronting the investigators, who needed a term to describe the material generated by the disaster, which hadn’t been seen before. However, it had been a worry for years that a disaster of the sort might happen, and a decade earlier China syndrome had appeared for a nuclear accident so bad that the core fancifully melted its way right through the earth.

The nuclear accidents at Chernobyl and Fukushima have also produced corium and the term has been used in the technical reports of both.

Incidentally, your dictionaries’ sense of corium, though not so rare as the nuclear one, is also unfamiliar to most people. These days, it’s more usually called the dermis, the “true skin” which lies beneath the surface layer that, logically enough, is the epidermis (Greek epi, upon or near). Corium is Latin for skin, hide or leather. It appears, somewhat disguised, in excoriate, literally to remove the skin but usually figuratively to criticise somebody so harshly that it feels like being skinned. Even more obscurely, it’s the source of cuirass, a piece of armour originally made from leather, and yet more so of malicorium, an old word for the rind of the pomegranate, which strictly speaking ought to mean an apple skin, as it’s from Latin malus, apple, though in antiquity any globular fruit could be called an apple.

7. Sic!

• James Pearce concluded from a link he saw on the Channel 7 website on 17 April that Australia must have a better class of miscreant: “Cars attacked by vandals wielding gold clubs.”

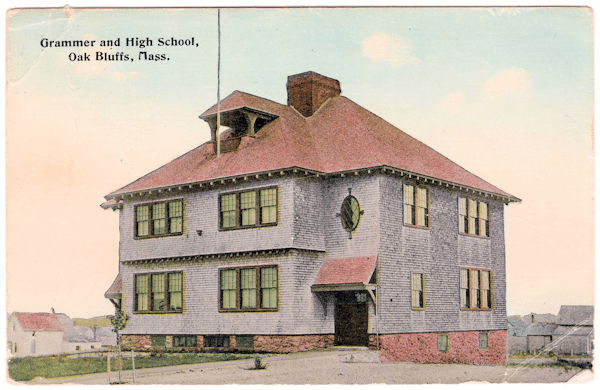

Spot the unfortunate error in this early twentieth-century postcard picked up by Bill Marsano in a Martha’s Vineyard flea market in 1976.

• Christine Shuttleworth was struck by this image in Mary Portas’s 2015 memoir Shop Girl: “Sprawling across two connected buildings and two floors, Jim founded Godfrey’s nearly 20 years ago.”

• A similar grammatical error appeared in a caption to a photograph of the Nazca lines, which Erik Kowal found on the Lifehack Lane site: “Only visible by air, generations of scientists and historians continue to be baffled by just how such etchings were made.”

• This headline on an American News article on 15 April was spotted by Paul White: “Defense Secretary Goes Rouge, Leaks Precious Information About Obama.” Red faces all round.