Newsletter 797

11 Aug 2012

Contents

1. Feedback, Notes and Comments

Binding cheese Jon Ackroyd commented, “A dear friend of ours in Vancouver used this very expression in conversation 45 years ago. I was about to mention this, but then I saw your comment from Mr Urdang in which he uses the phrase in the very context in which I first heard it. So I won’t mention it.” Thank you for not doing so. A robust refutation of Lawrence Urdang came from Paul Witheridge, who was born in 1943 in Toronto: “Rubbish! I’ve been familiar with the expression in Canada since boyhood and never heard it describe improved conditions. Rather, it is used as your correspondent cited: tighter or more challenging situations. My understanding of it has always been the constipation connection.” You may perhaps now better understand why the phrase confused me so much!

Adverbs in -lily Following up my snippet last week on friendlily, Arnold Zwicky pointed me to a Language Log column of his from March 2007 in which he includes a delightful extract from a piece by James Thurber about the utter unacceptability of such forms. You’ll find it at the end of his article. Anthony Allan e-mailed, “This item reminded me of instances when I’d wanted a more compact way of saying in a timely way. Timelily seemed awkward, but a South African friend suggested timeously. Would you care to elucidate?” With the aid of my trusty Oxford dictionaries, I can confirm the word exists, albeit mainly in Scottish use, with the sense “in good time; sufficiently early”. So it would be a useful substitute, if only it were more likely to be understood and less likely to be confused with timorously.

Correction The wind in California I mentioned in the williwaw piece was wrongly spelled. As Clark Stevens put it, “Around these parts, Santa Anna with a double n is the Mexican general remembered from Alamo times. The fire-fanning, east-to-west California wind is less one n, the Santa Ana.” This is taken by reference books to be from the name of the Santa Ana canyon, down which the winds blow, though they are known over a much wider area. Intriguingly, several readers argued it was neither, but santana, from the Spanish los vientos de Satanas, Devil winds. Some sources argue for yet a third source, Sanatanas, a corruption of a word from an unknown Native American language. I couldn’t possibly comment.

2. Weird Words: Strickle

For us moderns, this word hides its light under a bushel, which is appropriate because bushel and strickle go together like a horse and carriage or fish and chips.

A bushel is an ancient volume measure for dry commodities, wheat in particular, equivalent to eight English gallons or about 36 litres. In the proverbial phrase the bushel is the container for measuring out the wheat, eminently suitable for a light to shyly hide under. A true bushel was level measure, not heaped. The container was filled to overflowing and a straight-edged piece of wood, the strickle, was used to push off the surplus corn that stood above its edges.

The Oxford English Dictionary traces it to Old English, though then it meant a pulley or a teat. It is very probably not the same word. Wooden tools of similar kind are recorded in English dialect under names such as strike, stroke, strick and stritch. Scots have straik in senses that match, such as straik measure for level measure; this seems to be from stroke. It’s more likely that strickle is from the action of striking off surplus material. However, the bushel container was also known as a strike, from the old Anglo-French term estrike, so strickle and its variations may instead be from that.

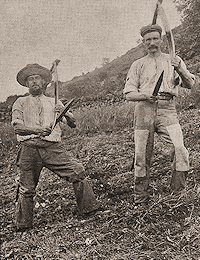

These two men are using strickles to sharpen their scythes during haymaking.

These two men are using strickles to sharpen their scythes during haymaking.

The otherwise incomprehensible English pub name Bushel and Strike comes from the measuring process, though it’s uncertain whether it refers to the container and its wooden tool or to two names for the container.

Strickles have turned up in all manner of trades, such as a tool in thatching or for trimming flax, a pattern or template in carpentry or a straight-edge for levelling sand in moulding. Another agricultural sense is linked to haymaking and harvesting. This description of it is from a historical novel set in the time of King Arthur:

It was hard work done with a short sickle that had to be sharpened constantly on a strickle: a wooden baton that was first dipped in pig’s grease, then coated with fine sand that put a keen edge on the sickle’s blade, though the edge never seemed sharp enough for me.

The Winter King, by Bernard Cornwell, 1995.

3. Topical Words: Whiff-waff

Alexander Boris de Pfeffel Johnson, Mayor of London, has had a good Olympics. He was in the news almost every day through his popping up in bumbling good humour in the media and at many events. Even his being stuck on a zip-wire 15ft above the ground on the banks of the Thames for several minutes, which would have been a humiliating catastrophe for most politicians, was salvaged by his banter with the watching audience.

Another frequent reference to him in news reports in the past two weeks has been to his speech at a party to mark the handover of the Olympic flag at the end of the 2008 Beijing Olympics. He declaimed, “Ping-pong was invented on the dining tables of England, ladies and gentlemen, in the 19th century. [CHEERS] It was, and it was called whiff-whaff.” Experts jumped on him at the time, telling him he’d got his facts wrong. Chuck Hoey, Curator of the International Table Tennis Federation’s Museum in Lausanne, wrote a heavily illustrated article setting out all the facts, which he entitled Boris Johnson and the Whiff-Waff Gaffe.

Yes, Whiff-Waff. No second h. Every journalist who has written of Whiff-Whaff in recent weeks has spelled it wrong (including those on 28 July who reported the claim by the French ambassador to London, Bernard Emié, that table tennis was invented in France, which led to a furious rebuttal by Johnson). We probably can’t blame Boris for the way the Beijing reports were spelled, as his comments were on TV and reporters naturally wrote it the way it sounded through the overwhelming influence of standard word reduplication. However, Boris did use the whiff-whaff spelling in his book Johnson’s Life of London of 2011. There’s nothing new in the error — every reference I’ve found on both sides of the Atlantic going back to the 1930s has included both hs.

Mr Hoey explained that Whiff-Waff was actually a latecomer to the game, being registered as a trademark by the British manufacturer Slazenger on 31 December 1900. I have failed to find any newspaper references to the product or even any advertisements for it, so must assume it was utterly unsuccessful. The name survived better in the US than in the UK, which is perhaps why one French website suggests that it was an American invention. Unlike Whiff-Waff, the name of the competitor trademarked by Hamley Brothers of London four months earlier has entered the language: Ping-Pong. A onomatopoeic allusion to the sound of ball on bat and table, the name seems to have been known rather earlier to describe an improvised indoor version of lawn tennis (in tradition, played by bored army officers using balls made from champagne corks and bats fashioned from cigar box lids).

Gossima was just one of the games being promoted by Jaques and Son for Christmas 1898. This advertisement appeared in The Graphic on 10 December that year.

Jaques and Son, also of London, brought out Gossima in 1891, which had some success, though a decade later it was incorporated into Ping-Pong, being sold for a while under both names. The true creator of the game, Mr Hoey explained, was the unsung David Foster, who patented a version in 1890 but had no commercial success with it.

Incidentally, the name now standard for the game, table tennis, is recorded from the late 1880s for a number of games, including one whose description reads like a cross between tabletop lawn tennis and billiards (using cues, not bats), and one that was in essence tiddlywinks. But when Gossima was noted in The Graphic on 3 December 1892, it was described as “a new table-tennis game”, which showed that the word had by then become known to mean something near its modern sense — illustrations show Gossima was essentially the game we now know.

The one unexplained issue is why Slazenger should have come up with such an odd name as Whiff-Waff. The Ogden Standard-Examiner of Utah reported in 1966 that the US Table Tennis Association had said it was because of the knitted web ball it used. (Before celluloid ones were introduced in 1901, players had used rubber balls or cork balls covered with a net.) That may explain the whiff (a slight gust of wind) but not the waff, though that’s a Scottish word meaning a waving movement, as of the hand, a relative of waft. It’s just as likely (that is, not very) that it’s from the English dialect term, whiff-whaff, known also in the US at the time, meaning trifling words or actions. That really would put the game in perspective.

4. Questions and Answers: Speaking out of school

Q From Kristin Hatcher, Michigan: I have searched your site but can’t find any information on the phrase speaking out of school. In my experience it is used to indicate that the speaker may not have the right to give the information they are about to give, or even that they are not certain the information is correct. Where did this odd phrase originate?

A I know of three versions of this saying, the other two being talking out of school and telling tales out of school.

The last is by far the oldest: it’s recorded from The Practice of Prelates, a bitter polemic by William Tyndale that was ostensibly about whether Henry VIII’s divorce from Catherine of Aragon was valid. In it, he says, “So what cometh once in may never out for fear of telling tales out of school.” It was presumably by then already a well-known aphorism, as John Haywood included it in his Dialogue Containing the Number in Effect of all the Proverbs in the English Tongue only 16 years later, in 1546.

The usual meaning is, don’t gossip indiscreetly or reveal private matters, secrets or confidences. Telling tales, revealing the misdeeds of a colleague or fellow pupil, has of course anciently been a heinous crime, since it broke the bonds of fellowship and mutual support.

The other two versions are by comparison mere Johnny-come-lately upstarts on the linguistic scene, no more than restatements of the older form. Talking out of school is by a few decades the older. I have an example from a US newspaper in 1863, but it’s recorded — rather obliquely — a little earlier from a British publication:

School politics in Prussia. — The Prussian State Gazette contains an ordinance prohibiting all talking about politics in schools. We are unable to inform our readers whether riding-schools and schools for scandal be included in this prohibition. It, however, appears to us that it would have been much wiser to have prohibited politicians from talking out of school.

The Athenaeum, 17 Aug. 1833. Schools for scandal is clearly enough a reference to the Sheridan play, but is there some unsavoury connotation to riding schools?

Your version, speaking out of school seems to be natively from the US, as it very rarely turns up in British sources even today, and then usually in the quoted speech of Americans. Here’s a recent example of it:

So, if Biden wasn’t acting at the behest of the White House, the next question is whether he was simply speaking out of school, which he has turned into something of a cottage industry over his long political career, or whether he was doing a bit of 2016 positioning.

Washington Post, 11 May 2012. Vice President Joe Biden had announced his support for same-sex marriages before President Obama did so.

5. Sic!

• Spence Putnam wondered if his local law had gone on a binge after reading this police press release in the Burlington Free Press of 4 August: “Although apparently intoxicated, Vermont law does not allow for someone to be charged with DUI [Driving under the influence] for operating an electric personal assistive mobility device.” (The electric personal assistive mobility device turned out to be a motorised shopping cart.)

• On a similar theme, the caption to a news video on news.com.au, dated 2 August, surprised Susan Bradley: “A Smart car has been in an unusual chase with Houston police after the driver evaded police driving under the influence.”

• Bob Coulter writes: “On August 5, a travel feature on Canada’s CTV News website referred to the Maldives as ‘a group of choral islands situated in the Indian Ocean.’ If we can’t get there to hear them live, do you think we could buy a CD?”

• Following the incident at the Olympics 100 metres final on 6 August when a bottle was thrown onto the track, we learn — thanks to Pete Jones and Anthony Massey — that a headline on the BBC News website ran: “Olympics: Man accused of 100m bottle throw”. If he’s that good, he should be in the Olympics rather than the dock.

• Leslie Tomlinson found an Olympics report on the website of the Toronto Star about a Canadian horse named Victor being found to have a “boo-boo” on its front left hoof, as a result of which it was refused permission to compete. The report stated, “There was no accusation of malpractice but the judge was deemed unfit to compete by the Games jury.” Which was very much the view of the Canadian team, I believe.