Newsletter 802

22 Sep 2012

Contents

1. Feedback, Notes and Comments

Hoity-toity Harry Audus asked “It seems too much of a coincidence if hoity-toity has nothing to do with haughty. What do you think?” The idea behind haughty is the same one of superiority as that of the modern sense of hoity-toity. It’s more direct, as haughty derives directly, via Old French, from Latin altus, high.

“Thank you for your definitions and depictions of hoity-toity”, wrote Kim Vares. “They’ve brought a smile to my face and a warmth to my heart. My mother, recently passed, often referred to those socializing with the elite as ‘hob-nobbing with the hooty-snoots’. A descriptive judgement somewhat similar to your explanation of hoity-toity and one that we used to giggle over.”

Lucie Singh wondered if hoity-toity was “at the heart of so many people thinking that hoi polloi means the upper crust (often perceived to be haughty etc) rather than the great unwashed? This misapprehension is rampant in the States.”

Grand slam Several readers repeated a comment widely attributed online, that O B Keeler of the Atlanta Journal used grand slam to describe the success of golfer Bobby Jones, who in 1930 won all four of the major golfing titles (British amateur, US open, British open and US amateur). The term was actually in wide use from about July that year as Jones won successive tournaments and the expectation increased that he would succeed in all four. This is how one newspaper of a great many described the culmination:

Bobby Jones swamped Gene Homans, 8 and 7, today in the finals of the U. S. amateur championship thereby completing his unparalleled “grand slam” in golf for 1930.

Beatrice Daily Sun (Nebraska), 28 Sep. 1930.

I’ve since found that it was also being used in other contexts for a team that won all its matches in a contest: it certainly appeared in reports about Davis Cup matches earlier the same year, so predating its use for the grand slam tennis singles titles.

James Swenson commented that “a grand slam in baseball — scoring four runs in a single time at bat — is the supreme accomplishment: four is maximal. In the US, later usages are strongly influenced by baseball: it seems to be important that one is achieving exactly four things (or occasionally three of some four, as a concession to difficulty). Examples at Wikipedia include tennis, NASCAR stock car racing, golf, fly-fishing, professional wrestling, men’s curling, and ultra-running. I would find it hard to assign the name grand slam to a new feat unless it had some basic fourness.”

The article contained my Error of the Week, as many readers noted, including Mary Donnelly: “Australians would love to have had Donald Budge as their own, as you mentioned in this post; however, he was an American.”

Lol! Simon Cochemé wrote, “You mentioned a popular text-speak abbreviation — LOL. This has been used by bridge players for at least 40 years for little old lady, a weak player of either gender.”

Sic! In response to one of my items last week, Ian Dalziel wrote, “Speaking as one approaching that milestone, the percentages of ‘those aged 65+ in long-term care facilities’ present no conundrum. The responses were clearly: 21% — Male; 31% — Female; 48% — Can’t remember right now — it’ll come back to me.”

2. Weird Words: Perissology

I come to this word in the hope that the piece you are about to read won’t be an example of it. Perissology means using more words than necessary to explain one’s meaning, a pleonasm. Since perissology is three letters longer than pleonasm but means the same, you may argue it’s an example of the related habit of using long words when shorter ones will do.

The word comes to us from the post-classical Latin of the fourth or fifth century AD. Romans of classical times knew it as a Greek word, perissologia, which came from perissos, beyond the usual number or size, redundant, superfluous. The prefix perisso- is known in two other very uncommon English words: perissosyllabic, a line of verse that has more syllables than normal, and perissodactyl, a grazing mammal with hooves made up of an odd number of toes, which sounds obscure but is a characteristic of horses as well as tapirs and rhinoceroses. Its opposite is artiodactyl, having an even number of toes, which refers to mammals such as pigs, deer, goats and cattle.

Perissology came into English at the end of the sixteenth century but was never anything more than an obscure literary word. In recent centuries it has mainly been exploited for humorous effect.

His inscience of avitous justicements, and of lexicology, his perissology and battology, imparted to his tractation of his cause, an imperspicuity which rendered it immomentous to the jurator audients.

Letters to Squire Pedant, by Samuel Klinefelter Hoshour, 1856. This described a lawyer pleading his case. It says that his knowledge of old judgements and the nature of words, plus his unnecessary repetition, made his case so obscure the jury decided it was unimportant. Battology is another word for perissology; hair-splitting scholars find a distinction between battology, perissology and pleonasm, but we may let that pass us by.

3. Wordface

Cheek by jowl Graham Thomas asked about a word that he had come across in correspondence of 1899 between the owner of Strachur House in Argyll and his builder about constructing dormer windows. It looked like haffit. The Oxford English Dictionary has it as haffet, a Scots and northern English term for part of the face, variously the side of the head above and in front of the ear, the cheek or the temple. In local building terminology, it referred to the protruding side and top frames of the dormers. The Concise Scots Dictionary marks it as chiefly literary, doesn’t mention the building sense, but says it has meant a side-lock of hair or the wooden side of a box-bed, two senses not too far from the one given in the OED. The latter’s entry says it comes from Old English healfhéafod, the fore part of the head or the sinciput. That last word improved my vocabulary: it transpired that it names the upper forward part of the skull, roughly from the forehead to the crown of the head; it comes from Latin semi, a half, plus caput, head. (The back of the head is the occiput, from Latin ob, towards or against.)

Media multitasking The rise in smartphones, tablets and other mobile devices that can easily be used while watching television has led to second screener for a person who comments on social media such as Twitter and Facebook about their viewing experiences while they’re watching the programme, or who searches out information to follow up what they’ve heard. The process is second screening, though the term companion experience has been used, especially by the BBC.

4. Questions and Answers: Hootenanny

Q From Steven Hancock: How did hootenanny arise?

A This is an example of a rule I deduced from extensive experience many years ago: that the shortest questions are the most trouble to answer. The quick reply is that we don’t know for sure. But its history is rather curious and worth exploring.

Hootenanny is a successful American linguistic export. Many people throughout the English-speaking world are familiar with it as a term for what one dictionary on my shelves describes as “an informal gathering with folk music”. So it’s a pity we have no clear idea of its origin. (The suggestion that it refers to the figurative offspring of an owl and a female goat may be disregarded, even though in its early days it was written at times as hootnanny.)

The indications are that in a directly musical sense it began to become known from about 1940 onwards. The first examples are from a short-lived newspaper in Seattle:

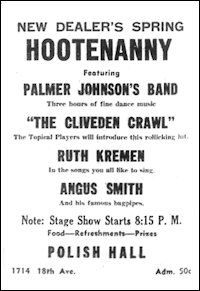

The New Dealer’s Midsummer Hootenanny. You Might Even Be Surprised! ... Dancing, Refreshments, Door Prizes.

An advertisement in the Washington New Dealer, 5 Jul. 1940, quoted in the Oxford English Dictionary. Another advert in the paper, from March 1942 (below right), lists dance music, singing and bagpipes as part of the event.

Despite this, the message from various archives is that it didn’t really begin to catch hold until the middle 1940s. The early examples, like the one above, referred to entertainments with no folk music content. Its link to folk evolved during the 1950s, with Pete Seeger often being linked to the shift; it was strengthened by the US television programme Hootenanny in the early 1960s. It had reached the UK by the late 1950s:

All over the British Isles today at ceilidhes, hootennanys and similar gatherings in pubs, clubs and private houses, folk music is flourishing as it has not done for over a century.

The Times, 10 Jan. 1959.

However ... in various spellings the word was around both earlier and later as one of those incoherent terms for a thing whose real name is unknown or momentarily forgotten. As an example, American newspapers ran a syndicated piece in the late 1930s about a man trying to teach his wife to drive. This extract gives its flavour:

When it starts you push down on the doo-funny with your left foot, and yank the uptididdy back, then let up the foot dingus and put your other foot on the hickey-ma-doodle, don’t forget to push down on the hootananny every time you move the whatyoumaycallit and you’ll be hunkydory. Gosh, dear, what’s the matter, haven’t you been listening to me?

Centralia Daily Chronicle, 10 Jul. 1937.

In the journal Western Folklore in 1963 the American researcher Peter Tamony argued it should be classed as “an indefinite American word” that meant what you wanted it to mean. There’s no shortage of ways it was applied. It could be a device to hold a cross-cut saw in place while sawing a log. The lexicographer Jonathon Green found a reference to it in a newspaper of February 1918 in Lincoln, Nebraska, as a slang term of US soldiers for cooties (body lice). A play by J C McMullen of 1920, Turning the Trick, includes the lines “‘Have you any visitors at present?’ ‘No one. Wait a minute though. I forgot that bolshevik hootenanny Kathleen’s brought in’”; the young woman so described is rebellious (one sense of Bolshevik at the time, abbreviated to the British bolshie) as well as wild and unconventional and is seen as a bad influence. Another sense, of an ignorant or stupid person or clod, is recorded from about the same period in rural Ohio.

The form hootin’ nanny appears in newspapers from 1919 onwards as a slang term for a motor car. I’ve found that it referred also to other varieties of noise-making machines, including a railway locomotive and a home-made musical instrument. Other sources claim hootin’ nanny was earlier a southern US dialect term for a slatternly or talkative woman. In October 1929 the Evening News Journal of Clovis, New Mexico, mentions a visit by a sextet called Hooten-Anny at which “harmonious selections were sung”. Was the name a self-deprecating play on hootin’ nanny? It seems highly probable that this version of hootananny, whatever it first meant, came directly from hoot for a discordant noise. It may even have been the original from which the musical sense evolved.

There are other early music references. In January 1924, an advert in the Evening Gazette of Xenia, Ohio, told its readers that “Marion McKay and his Greystone Orchestra have recorded Hootenanny and Little Butterfly for Gennett Records”. A report in the Newark Daily Advocate in April 1921 noted that “the comedy sketch, ‘The King of the Hootananny’ written by Robert Abernathy and featuring several original songs, was the hit of the evening at every concert.”

There’s clearly more going on here than the printed record tells us. But what exactly that is remains largely obscure.

5. Sic!

• Judith Graham submitted this from the September Partners in Health e-newsletter sent out by Kaiser Permanente healthcare: “Top 5 reasons to get a flu vaccine ... Protect yourself from the flu and those close to you.”

• A report of 15 September on the BBC website about the attack on Camp Bastion in Afghanistan included this sentence, found by Ed Floden: “Earlier this year, a member of Nato forces was injured when an Afghan man drove a pick-up truck onto the runway, which then burst into flames.”

• In the 6 September issue of The Arbiter (the student newspaper of Boise State University) this headline startled Mike Lynott: “Sober or not, Health Services offers assistance.” If he ever needs help, he says, he will hope it’s sober that day.