Newsletter 860

30 Nov 2013

Contents

1. Feedback, Notes and Comments

Selfie Colin Houlden commented, “As long ago as the mid fifties, whilst serving in the Royal Navy, a self-photo was referred to as a me-graph. It would appear selfie is but a step away!”

Drowning, not waving? Several readers denied there was anything wrong with a headline in last week’s Sic! section: “Where someone drowns determines their chance of survival.” They argued that drowning isn’t necessarily fatal because victims can be resuscitated. I was so surprised that I checked the verb in numerous dictionaries. All the definitions include the word die, which reflects the everyday sense of the verb. Drowning may indicate a process but drown is surely final. I wonder if a shift in meaning is developing under the lexicographical radar?

Feghoots My piece on these mini shaggy dog stories gave readers a wonderful opportunity to quote their favourite elaborate puns, such as “Great auks from lid allay cairn’s groan”, “People who live in grass houses shouldn’t stow thrones” and “Honour’s tea is the best, Polly, see!” Jeff Lewis’s favourite tag line was a list of things Frank Muir had to attend to before his wife returned from holiday “Soup, a cauli, fridge, elastic, eggs, peas, halitosis”. Malcolm Ross-Macdonald remembered one with the punchline, “One Tooth Free For Fife, Sick Sven Ate Nine Tench.” No more, please!

It was a delight to discover that nobody wrote for an explanation of “male pheasants in orifice”; should you still be wondering, it’s an obfuscated reference to “malfeasance in office”.

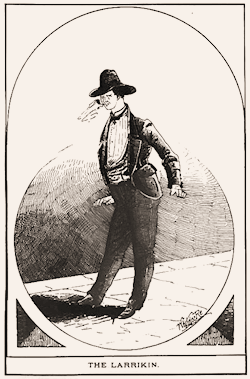

2. Larrikin

Larrikin is a quintessentially Australian term. It appeared in the 1860s for a street rowdy or urban tough. The writer Archibald Forbes described the larrikin as “a cross between the Street Arab and the Hoodlum, with a dash of the Rough thrown in to improve the mixture.” Vicious fights between larrikin gangs were common. In the late nineteenth century some gangs formed a subculture with a dress style that included broad-brimmed hats, gaudy waistcoats, strapped moleskin trousers and high-heeled boots.

Early suggestions of its origins were fanciful. The obituary in the Melbourne Argus in 1888 of a police officer named James Dalton said that he had accidentally invented it in a court hearing through a misunderstanding of his saying larking in his broad Irish accent. This was countered by a letter in a subsequent edition, which argued that it was from leery; the writer said it had became a catchword of Melbourne youths in the 1860s from its appearance in a popular London song, The Leery Cove. Locals started to call the boys leery kids, which was transmuted over time into larrikin. A related story of the same period was that criminals in local jails described themselves as leery kin, which was similarly amended through the Irish brogue of their jailers. Kin was also invoked in Larry’s kin, the supposed relatives of some unknown Australian. This has been linked to another Australianism, happy as Larry, recorded first around the same time as larrikin. The supposed connection with Irishmen in two of the tales has led to some writers on language declaring larrikin to be an Irish word.

We can dispose of all of these stories at a stroke by looking across the Tasman Sea. Larrikin is recorded in New Zealand in 1866, two years before Australia. There can be little doubt that the word had a common origin in the old country. The English Dialect Dictionary has larrikin as a dialect term of Warwickshire and Worcestershire for a mischievous or frolicsome youth. It would seem to have become significantly modified in sense during its journey to the Antipodes.

In modern Australian English, larrikin has been inverted into a term almost of respect. The old sense of a tearaway or hooligan has been replaced by that of a non-conformist and irreverent person with a careless disregard for social or political conventions, someone who may be thought truly Australian.

3. Wordface

Doggy blends Dog breeders who create crosses delight in inventing cutesy names for them, particularly if a poodle is part of the mix. The cockapoo is a poodle crossed with a cocker spaniel; a maltipoo is a poodle and Maltese terrier cross; the peekaboo is the offspring of a poodle and a pekinese. The Daily Mail recently reported on the newest: the cava-poo-chon is “a cavalier King Charles spaniel and bichon frise mix bred with a miniature poodle.”

Stanfordene The technical press has been excited this week at the implications of an announcement by researchers at the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and Stanford University, who predict that a material as yet unmade has high promise for the next generation of computer chips. It’s a two-dimensional single layer of tin atoms, which theory suggests will conduct electricity with 100% efficiency at room temperature. Adding fluorine atoms could keep it working at the temperature of boiling water. It may not have been made yet but it already has a name, stanene, from the Latin for tin, stannum, plus the -ene ending from graphene.

Maxwell’s hammer I came across an odd British jargon term the other day: Maxwellisation process. This is lawyer-speak for a procedure by which individuals who are to be criticised in an official report are warned so they can respond before publication. The process is in the news at the moment in connection with the long-delayed report of the Chilcot inquiry into the causes of the war in Iraq. The term can be found at least as far back as the early 1990s but its origin lies in a court case of the early 1970s brought by the media mogul Robert Maxwell. He had been severely criticised in a government report and argued that it was against natural justice not to have been given an opportunity to respond before the report was published.

4. Thirteen and the odd

Q From Robert Visconti: In Melancholy Dane, Damon Runyon describes folks waiting to enter a performance of Hamlet dressed “in the old thirteen and odd.” What a curious construction! Where does it come from?

A This is the full quote from the short story:

Well, I finally go to the theater with Ambrose and it is quite a high-toned occasion with nearly everybody in the old thirteen-and-odd because Mansfield Sothern has a big following in musical comedy and it seems that his determination to play Hamlet produces quite a sensation.

The Melancholy Dane, by Damon Runyon, in Collier’s Weekly, 18 Mar. 1944.

I mentioned this in a piece back in 2006 about soup and fish, the Wodehousian slang term for evening dress, because I had come across it in the same context. I couldn’t make head nor tail of it then and time was too short to enquire. Having now done so, I’m not much further forward.

It’s slang of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in the USA. The first instance that I’ve come across was in the New York Herald in September 1898 and the last — apart from Damon Runyon’s — was in a short story by George Ade, The Fable of Mr. Whipple’s Dress Suit, syndicated in newspapers in 1933. The dating suggests that the expression had already fallen out of fashion by the time Runyon used it; Jean Wagner’s assertion in a 1966 book about his slang that he had invented it is clearly mistaken.

An early example makes clear that the two slang terms refer to different things:

“Ain’t you dining out? What’ll I git you — the ‘soup-and-fish’ or the ‘thirteen-and-the-odd?’” Stephen disclaimed any desire for the dinner coat first mentioned, declaring his preference for the more formal tailed garment.

An Enemy to Society, by G Bronson-Howard, 1911.

Here, the thirteen-and-the-odd is clearly what we know as white tie or top hat and tails, a full formal evening dress of a black tail coat, white waistcoat, white bow tie and top hat. Soup and fish is a tuxedo or the equivalent called black tie because it is normally worn with a black bow tie. But an earlier example (found for me by Christopher Philippo) contradicts this:

“Tod” was as graceful and courteous as it is possible to be. He shook hands with this man and that woman, then went to his room and came down in half an hour dressed in his “thirteens and the odd,” as the boys around Saratoga call a Tuxedo and low cut vest.

New York Evening Telegram, 11 Aug. 1899.

After I mentioned it for the first time, several readers pointed out that the crackerjack uniform of junior enlisted men in the US Navy is fastened by a thirteen-button flap. This may be relevant, but probably not.

A card game of the same name is mentioned by a witness in a case before the supreme court of Alabama in 1855, who claimed that it could also be played with dominoes. Nobody else mentions the domino version but the card game is described in a number of American compendia, such as The Modern Pocket Hoyle of 1868. It was a version of whist for two people, who were each dealt 13 cards, with another turned up on the pack to indicate trumps. Hence, I suppose, thirteen and the odd.

It’s possible that the black-and-white of the cards (or dominoes if the game was more common than the references imply) was transferred by analogy to formal dress. The written evidence hints that it was first used for the tuxedo, which was introduced at Tuxedo Park in New York State in the middle 1880s, but was later transferred to the formal white tie, with soup-and-fish taking over for the tuxedo.

The phrase is so curious and unusual that there surely must be some connection between the game and the dress styles. But the evidence is so sparse that as matters stand it’s impossible to be sure what was in people’s minds to link them.

5. Sic!

• Robert Kernish found this on the website of the Iron Hill Brewery: “We took Paul’s love of big west coast IPAs and Chris’ pension for dry, yeast-driven Belgians and came up with this American-Belgo.”

• Jeff Gale was reading the Wall Street Journal for 20 November and came across this mystifying headline: “Kiwi Up on China Baby Talk”. It turns out that the New Zealand dollar has gained value against the American dollar on news that China is relaxing its one-child policy. It seems that New Zealand supplies much of China’s milk.

• One of the editor’s picks on the ABC News site in Australia on 27 November read: “Captive-bred Tasmanian devils are thriving on their new island home, breeding and interacting with tourists.” Thanks to Rob Young for sending that in.

• “Beware of abusive rights groups,” was Frank Steele’s comment on an Associated Press headline on 25 November: “Zimbabwe Urged to End Abuses by Rights Group.”

• From the Vermont Eagle of Middlebury, Vermont, dated 30 November, spotted by Spence Putnam: “The complainant, Robert Evegan, reported he discovered two males breaking into a building on his property which fled once they were discovered.”

6. Useful information

World Wide Words is copyright © Michael Quinion 2013. All rights reserved. You may reproduce this newsletter in whole or part in free newsletters, newsgroups or mailing lists online provided that you include the copyright notice above. You need the prior permission of the author to reproduce any part of it on Web sites or in printed publications. You don’t need permission to link to it.

Comments on anything in this newsletter are more than welcome. To send them in, please visit the feedback page on our Web site.

If you have enjoyed this newsletter and would like to help defray its costs and those of the linked Web site, please visit our support page.