But and ben

Q From Jim Black: In Scotland, one may find a style of house known as a but and ben. That’s a curious term and I’m thinking it has an interesting history. Can you help?

A I can. It’s a phrase steeped in Scottish history and culture, traditionally crofting but also rural life generally. It can evoke a poverty-stricken hardscrabble life that has at times been romanticised, as in this song by Sir Harry Lauder:

Just a wee deoch an’ doris, afore ye gang awa’;

There’s a wee wifie waitin’ in a wee but an’ ben.

Deoch an doris, a custom of a parting drink, is from Scottish Gaelic deoch an doruis, a drink at the door.

A but and ben is a two-roomed house of one storey. There was usually only one door to the outside; this gave access to the kitchen, the public room in which everyday life took place and in which members of the family often slept. This led into a private inner room, where guests could be entertained and which — like many a front room or best room in poor but decent homes everywhere — was often furnished to a higher standard but less often used. If the family was large, however, the inner room could double up as a bedroom.

The outer room was the but and the inner one the ben. Putting them together the but and ben was the whole house.

The cottage had originally consisted of the usual “but-and-ben”, that is to say, in well regulated houses (which this one was not) of a kitchen — and a room that was not the kitchen. The family beds occupied one corner of the kitchen, that of Bridget and her husband in the middle (including accommodation for the latest baby), while on either side and at the foot, shakedowns were laid out “for the childer,” slightly raised from the earthen floor on rude trestles, with a board laid across to receive the bedding.

The Dew of Their Youth, by S R Crockett, 1910.

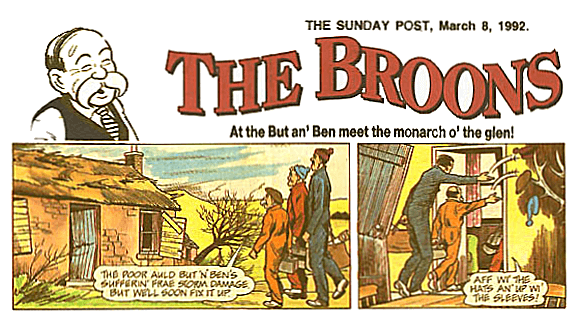

The survival of the term in Scotland has been placed squarely on the cartoon strip The Broons, which has appeared in The Sunday Post for the past 80 years. They live in the fictional Auchenshoogle, a name probably based on that of the Auchenshuggle district of Glasgow (though its location is never specified), but have a but an’ ben in the hills as a holiday home.

Some people have guessed that ben is Gaelic or from some Norse word. But there’s no evidence for either and the experts are now sure it’s a dialect variant of the Middle English binne, within. (If you know Dutch or German, you will be familiar with its relative binnen with the same meaning.) But is a special instance of our everyday conjunction, which stems from the Old English be-utan and which variously meant without, except or outside.

So the but was the “outside” room and the ben the room “within”.

This led to various phrases. Both words were used in the extended phrases but the hoose and ben the hoose for the two rooms. To be far ben with one meant to be a close friend, who was regularly admitted to the ben. To go but and ben was to move from the inner to the outer room and back again, hence repeatedly going backwards and forwards, to and fro. Since the but and the ben constituted the whole house, but and ben could also mean everywhere.

Blithe, blithe and merry was she,

Blithe was she but and ben:

Blithe by the banks of Ern,

And blithe in Glenturit glen.

Blithe Was She, by Robert Burns, in The Works of Robert Burns, 1800.

Families occupying two-roomed apartments in tenements, which led off a common passage as close neighbours, were said to be living but and ben.