Newsletter 724

19 Feb 2011

Contents

1. Feedback, notes and comments

Saucered and blowed The piece last week about this American idiom provoked a lively correspondence from readers who remembered the technique being used by members of their families. Reports of the technique also came from Sweden, Russia and other countries. David A Bagwell recalled a story about George Washington, who is said to have observed that the US Senate should serve as a saucer to cool the impassioned legislation coming from the House. This is the earliest example of it I can find:

“Why,” asked Washington, “did you just now pour that coffee into your saucer, before drinking ?” “To cool it,” answered Jefferson, “my throat is not made of brass.” “Even so,” said Washington, “we pour our legislation into the Senatorial saucer to cool it.”

Republican Superstitions as Illustrated in the Political History of America, by Moncure Daniel Conway, 1872.

Beverley Charles Rowe wrote, “I’m reminded of the joke about the man castigated for drinking out of his saucer who protested that if you drank from the cup you got the spoon in your eye.” Crawford MacKeand remembered the column about a snack bar, Snax at Jax by Alan Hackney, which appeared in Punch in the 1950s. One of the regulars at the bar saucers and blows his tea. This incurs the ire of his mate, who tells him it isn’t good form. He asked what he was supposed to do and got the answer “Fan it wiv yer cap mate, fan it wiv yer cap!”

Data Several readers queried my writing in the last issue, “The data so far is unsurprising” because for them data is plural. It may be worth noting that British non-specialist usage has settled on data as a singular mass noun.

2. Weird Words: Spissitude/ˈspɪsɪtjuːd/

In January 1924 the Atlanta Constitution reported that spissitude had been added to others, such as thermometer and truly rural, as words the New York police used to test the sobriety of midnight revellers.

Dr Henry More, a specialist user

of spissitude

What the word meant was irrelevant, even if any midnight reveller knew it or was in a fit state to define it. It was enough that it contained those hissing sibilants that make it sound like a curse. In fact, it’s respectably scholastic and technical, though hardly common. In brief, the spissitude of a material is its density, thickness or compactness.

It is to the molasses chiefly, which gives a spissitude to the beer, that the frothing property must be ascribed.

A Treatise on Adulterations of Food, and Culinary Poisons, by Fredrick Accum, 1820. His book described the horrific compounds commonly added to food and eventually led to the first public health legislation.

It appears most often in books about the history of philosophy and spiritual thought that discuss the ideas of Dr Henry More. He was a seventeenth-century philosopher, for whom spissitude was a fourth dimension that allowed supernatural spirits to occupy a material place at will.

This is a rare modern appearance of the word:

From the same tree he untied a length of rope and followed the line of wire, string, strips of sheet and chain into the trembling spissitude of the swampland, reeling in the line as he went.

And the Ass Saw the Angel, by Nick Cave, 1989.

Its source is the Latin inspissare (based on spissus, thick or dense), which is also the origin of the English verb inspissate, to thicken or congeal.

3. Wordface

Titular oddities Yesterday, The Bookseller magazine announced its shortlist for the Diagram Prize, which showcases the strangest book titles of the year. A Mills & Boon bonkbuster, a guide to managing a dental practice and an examination of the ongoing debate surrounding organ procurement are among the titles. The literary award was conceived in 1978 to avoid boredom at the annual Frankfurt Book Fair and has been held in all but two years since. The shortlist is: : What Color Is Your Dog?; Managing a Dental Practice the Genghis Khan Way; Myth of the Social Volcano; The Italian’s One-night Love-child; The Generosity of the Dead; and the 8th International Friction Stir Welding Symposium Proceedings. Public voting is now open via a link on The Bookseller’s website. The winner will be announced on 25 March.

Inflationary suns Scientists have identified a type of star they are calling a bloatar, an unlovely name for one that has eaten its planets and become bigger and cooler than expected.

Digital eternity The US stand-up comedian Patton Oswalt coined the acronym ETEWAF in an article in Wired Magazine on 27 December last. It expands to “Everything That Ever Was — Available Forever”. It refers to the power of digital recording and the online world to make anything, from any era, instantly available. He is concerned about the potentially adverse implications for creativity: “Etewaf doesn’t produce a new generation of artists — just an army of sated consumers. Why create anything new when there’s a mountain of freshly excavated pop culture to recut, repurpose, and manipulate on your iMovie?”

Frankensteinian? The word anthropoeia has appeared several times in my reading in the past week, because it has featured in discussions of Philip Ball’s new book Unnatural. He invented it for the concept of artificially creating human beings by processes such as cloning. It’s from classical Greek anthros, man + poiein, to make (as in onomatopoeia, forming a word from a sound, and mythopoeia, the creation of myths).

4. Questions and Answers: Piss-poor

Q From Bob Fleck: An item circulating online under the title Interesting History claims, “They used to use urine to tan animal skins, so families used to all pee in a pot and then once a day it was sold to the tannery. If you had to do this to survive you were ‘piss poor’.” This screams of folk etymology. Can you offer real clarity?

A It certainly sounds like folk etymology, except that the piece is clearly a mischievous attempt to deceive its readers.

Tanners at work

As with other tongue-in-cheek suggestions about origins, a grain of truth exists. Urine has been widely used in many parts of the world in the preparatory stages of tanning, in particular to help remove the hair from hides before applying tanning agents. The Romans, as one example, systematically collected urine for this purpose (in the first century AD the Emperor Nero even put a tax on it).

However, the expression piss-poor is recent and has nothing to do with tanning. The current state of research suggests it may have been invented during World War Two, because the first examples in print date from 1946. Though it is still classed as low slang by dictionaries, its mildly unpleasant associations have become blunted by time and familiarity.

The origin is straightforward. Piss began to be attached to other words during the twentieth century to intensify their meaning. Ezra Pound invented piss-rotten in 1940 (the first example on record) and since then we’ve had piss-easy (very easy), piss-elegant (affectedly refined, pretentious) and other forms. Piss-poor just means extremely poor:

Larkin’s letters, wrote Philippe Auclair, writer and broadcaster, were “very funny, very beautiful, and very sad; the grace of an angel, the precision of a geometer, and the short-sighted, intolerant piss-poor idées fixes of a provincial buffoon”.

The Spectator, 27 Nov. 2010.

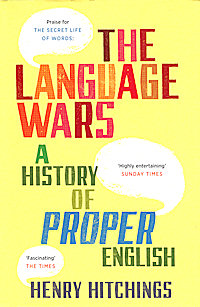

5. Reviews: The Language Wars

Henry Hitchings’s previous works include a biography of the man he wrote his PhD thesis on, Dr Samuel Johnson. Here he turns to the history of disputes about what constitutes good English. To call it warfare is to seriously overstate matters — nobody has ever manned a barricade in defence of the right to split an infinitive — but publishers do like catchpenny titles.

He unpacks the history of proper usage, occasionally diverting to offer up examples from other languages as mirrors to English. He shows that complaints about the decline of our language are almost always illogical, that later generations frequently find the view of pundits to be either irrelevant or risible and that attempts to hold back change are futile. He is sympathetic to the view that there is nothing absolute about grammar; its rules are not laws of nature but conventional beliefs which are modified through changing fashion and shifting everyday use.

Debate over meaning and standards isn’t peculiar to our times. But today’s prescribers and proscribers may be surprised to learn for how many centuries the idea of good usage has been debated and how much standards have varied. As one example, the apostrophe has been the subject of unending debate since it was first used in English in 1559 (the next century, John Donne could write “any mans death diminishes me” without needing it). Writers in the early eighteenth century used it to mark the plurals of nouns. It wasn’t until the late nineteenth century that usage settled down. Today’s mistakes with it aren’t a sudden eruption of ignorance but a continuation of misunderstandings and differences of opinion that are centuries old. The author believes the apostrophe is likely to disappear, not least through a desire for crisper design and less cluttered pages.

The value of individual words has long been debated, often with a sense that there are good words and bad words. The history of such objections shows how ill-judged most of them are. Eric Partridge hated economic. Fowler objected to gullible, antagonise, placate and transpire. Last century, as they became known through the talkies and other imports, British writers complained about Americanisms such as reliable, lengthy, curvaceous, hindsight and mileage. In 1978, the Lake Superior University Banned Words unavailingly deprecated parenting and medication. Conversely, many Words of the Year selections (pod slurping, locavore) show that the usual fate of new words, even fashionable ones, is obscurity.

We all speak more than one variety of the language. We pitch our vocabulary and style to suit our hearers, whether those are our children, our friends, our colleagues or the unseen readership of public prose. Standard English has the highest prestige, the one appropriate to formal communication, and the one we need to master if we’re to be taken seriously in that world. But it’s useless to apply the rules of standard English to the informal registers of conversation or of slang and dialect. Hitchings argues that — in spite of widespread condemnation — instant messaging, textspeak, with all its abbreviations, informality and often casual disregard for the rules of the standard language, doesn’t degrade English. He contends that the people who use it are easily able to distinguish it from the language needed in an essay or report.

Some parts of The Language Wars will be familiar to anyone who has read previous works on the evolution of language. But Hitchings provides a wealth of examples to illustrate his points. He writes well and is never dull. Even if you’re predisposed to disagree with him, he’s worth reading.

[The Language Wars: A History of Proper English by Henry Hitchings, published by John Murray in the UK on 3 Feb. 2010; hardback, pp408, including bibliography and index; publisher’s UK price, £17.99; ISBN 978-1-84854-2082.]

6. Sic!

• Anne O’Brien Lloyd e-mailed from Saskatoon, Canada: “Discussing the benefits to be obtained from the sharing of technical information among police forces, a representative of one force noted on CBC radio last week that there would be lots of cross pollination and that there would be plenty of grist to their mills so they wouldn’t be re-inventing the wheel.”

• The description of a recipe for a savoury pie on the WebMD website left Thomas Seng wondering about its appeal: “Invented out of the need for a one-dish supper, it’s light and easy and guaranteed to leave you with leftovers.”

• Belinda Hardman suggests that the headline over a story dated 9 February on the MedPage Today site implies that membership in the Benjamin Button club comes at too high a price: “Stroke Patients Getting Younger”.

• It happened a month ago, but the story Don Doherty tells us about is still worth repeating. During the devastating floods in Queensland, Australia, the front page of the Morning Bulletin of Rockhampton on 6 January included the headline “30,000 pigs swept away in flood”. The next day, the paper featured this correction: “What Baralaba piggery-owner Sid Everingham actually said was ‘30 sows and pigs’, not ‘30,000 pigs’.”