Gordon Bennett

It’s getting passé now, but it was common in the last decades of the twentieth century to hear British speakers say Gordon Bennett! when they wished to express surprise, incredulity, or exasperation. “Gordon Bennett — he couldn’t even keep himself sane, let alone anyone else,” as a character says in Red Dwarf by Grant Naylor. The expression has long puzzled lexicographers.

There was a real person, named in full James Gordon Bennett. Confusingly, there were two of them, father and son. Bennett the elder was born in Scotland in 1795, emigrated to the US, became a journalist, founded the New York Herald in 1835, and instituted many of the methods of modern journalism, or at least “journalism for the frankly ignorant and vulgar”, as H L Mencken called it in The American Language in 1921, or the “yellow press”, as others called it, from an early attempt at colour printing by the New York World in 1898. His son of the same name (known as Gordon Bennett to distinguish him from his father) was also a proficient journalist (he sent Stanley to Africa to seek out Livingstone) but preferred the good life, mostly in London and Paris. He spent much of the fortune accumulated by him and his father in promoting air and road racing in England and France and generally being the playboy.

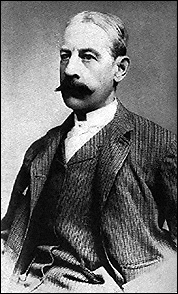

James Gordon Bennett the younger

James Gordon Bennett the younger

There are several surviving pieces of evidence that show the high public profile of Gordon Bennett the younger during his European years, and his impact on sports in particular. He can be said to have started international motor racing through his sponsorship of the Bennett Trophy races from 1900 to 1905; a trials course in the Isle of Man was named after him. He gave a trophy for long-distance ballooning in 1906 that started the modern sport (the international Gordon Bennett balloon race still continues). He also gave a cup for powered air racing. So it’s not surprising that his name become widely known in Europe, well enough that he should have become a byword, helped by his eccentric and boorish ways (he is listed in the Guinness Book of World Records under “Greatest Engagement Faux Pas” for having his engagement to Caroline May broken off in 1877 after he arrived late and drunk at the May family’s New York mansion and urinated in the living room fireplace in front of his hosts).

The curious thing is that though his high-living European heyday was in the first decade of the twentieth century, the exclamation only began to appear in print much later. Until a find by the BBC television programme Balderdash & Piffle in 2007, the earliest example in the Oxford English Dictionary was in a cartoon caption dated 1983. It is now known to have appeared in a 1937 novel, You’re in the Racket, Too, written by a little-known London-based writer, James Curtis: “Gordon Bennett. He wasn’t half tired.” Even then, the expression must have been lurking in the spoken language for at least two decades (Bennett died in 1918) before it was put down on paper.

His strong European connections explain why the exclamation Gordon Bennett should be known in Britain but not in the country of his birth. Though Gordon Bennett is a satisfactory exclamation in its own right, its popularity was surely helped along because it echoed such mild oaths as God help us or Gor blimey. I’d guess that Gordon Bennett started to be used as a humorous reference to such imprecations.

There was also an Australian general of the same name, who controversially left Singapore after the Japanese reached it in 1942, abandoning his men. Some writers have in the past wondered whether this might have been the real source of the exclamation, but the discovery of the 1937 citation rules it out, though it might be that the general’s notoriety gave a fresh impetus to the expletive in Australia.

Gordon Bennett may have had another influence on the language. Until the middle of the nineteenth century, the given name Gordon was unusual. It turned up mostly as a family name, originally Scots, deriving ultimately either from the town in Berwickshire or from a similarly-named place in Normandy (experts disagree). Our Gordon Bennett, like his father, had it as his middle name, which had probably been bestowed originally to mark the family name of some relative of influence. The popularity of Gordon as a given name grew as the nineteenth century waned. It has been suggested that this was through the influence of Charles George Gordon, Gordon of Khartoum, the soldier of the British Empire also known as Chinese Gordon, once hugely famous, who died during the siege of Khartoum in 1885. But could it be that the popularity of the name was due in part to the publicity given it by Gordon Bennett only a few years later?